Poisoned Chalice

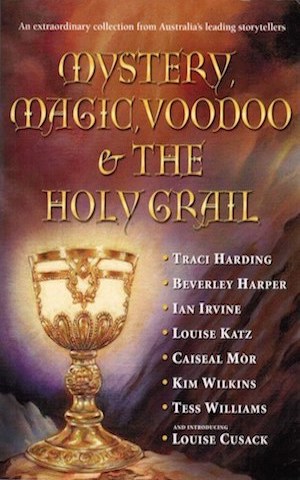

My first shorter story – a rather dark dystopian SF thriller novella. First published in the anthology, Mystery, Magic, Voodoo and the Holy Grail, 2000. The two main characters also appear briefly in The Life Lottery.

Author’s note

This is the unedited version and probably contains the odd error and typo. The corrected manuscript was donated to Fisher Library at the University of Sydney along with other papers from the period, and is not readily available to me.

1: The Physical

1: The Physical

I don’t deserve to live.

I want to but I have no right. I’ve always known that. I’m a defective, you see. A cripple. Short leg, twisted foot, extra toe. An it.

I should have been smothered at birth. How could my mother have kept such a thing? How did she get me through the physical?

I’m not well-educated, no chance for that, but I read. I know that once the deformed were only stared at, or ignored, or kept out of sight. I’ve even read, though it must have been a lie, that there were places where people like me had a right to work, to play, even to mate. Not even I could come at that though. No one could, since the Genes Act.

I ruined my mother. She had to leave her wonderful job at the University, her friends, her beloved Sydney. Anyone might have betrayed me. Then, termination for me.

*

We went to live in a shack up the north coast, in the mountains. In the summer it rained so much that mould grew on the walls. On winter nights even the water in the toilet froze solid, and the only warm place was in her arms. My mother became a drab and a drudge, living on her wits, an occasional gentleman caller, and a scabby vegetable patch. She could get no social security for me — the annual physical, remember!

She cut off the extra toe when I was a baby — I never remember having it. But how could I forget her next attempt to make me normal? She broke my foot and my ankle, forced them into the right shapes and plastered them up for a month, until they healed.

It didn’t work. My foot looks like a wrung-out cloth; my ankle is a gnarled lump. It still hurts like blazes when I walk, though with a special boot I can almost conceal the limp. I tell people that I had an accident when I was a child. But the doctors who do the physical won’t be fooled.

She died when I was fourteen. Just willed herself to death, refused to eat. I suppose she couldn’t stand the shame any longer. Her only bequest was a Citizen’s Card in my name, good for five years. How did she manage it? I’ll never know. She was a very clever woman, my mother, and good with computers. But a failure with bones.

*

No one with a card can go more than five years without a physical. Without a card you have no education, no social security, no job but the ones that no one else will do.

The card got me a bit more school, just enough to show me what I can never have. So I went back to the city and found one of those jobs. It’s a miserable living, packing things in boxes, but it doesn’t require the physical.

I sometimes walk up Parramatta Road to the University, where my mother worked. I love the old yellow stone, the calm, the sacred aura of books. Once I even dared to go inside, and there was a jacaranda tree in flower. How I yearn for the place, but that is impossible. I think you know the reason by now.

*

More than four years have gone by since she died. Soon the computers will call me to the physical. And then?

Australia is a civilised country. A panel of doctors, all the evidence reviewed, process followed to the letter. After all, it could have happened in an accident, my deformity. X-rays, ultrasound, gene testing, whatever that is.

Finally, by letter — ‘We regret to inform you …’

Apparently scientists know which genes are no good. The law allows no option, if you have bad ones. I understand that. I don’t want us to become a race of monsters.

Termination. But in a very civilised way. Our society doesn’t care about a lifetime of suffering, but it insists that my death be painless.

I still don’t want to die.

*

Happy birthday! Nineteen today.

And I’ve found the answer, shameful and shocking though it is. I will have a baby. Our civilised society would not terminate a mother with a baby to look after. Surely not!

*

I’ve got a mate. I chose him with care, from the small pool I can fish in. Of course I’m not tall, or pretty, or clever with words or glances, but I’m told I have a nice face and a sweet smile. I’m a woman, in spite of my handicap.

He, on the other hand, was just a youth — big ears, freckles, shy, bewildered eyes. He had no defects, though.

He knew even less about it than I did, but he learned quickly enough, and it was warm in his arms. I liked that part very much, the sex. I loved to take him in, enclose him within me, knead him. It would have been good to do more of that, but each time was a risk. One day he would no longer be happy to do it in the dark. I couldn’t bear to see his disgust when he realised what I was like.

As soon as I was sure about the baby I had to break with him. I tried not to hurt him, but I did. I loved him, in a way.

There was a physical for pregnancy too, but I got through that all right. They didn’t tell me to take my socks off.

*

Twelve weeks, and I bled and bled. I was sure I would lose my beautiful baby, my saviour, but it was loyal. It knew my need and wouldn’t abandon me.

*

Now I’m four months gone. Strangely, no letter has come. No physical. Maybe they’ve lost my file. Maybe I didn’t need the child after all.

*

Labour day. A home birth. They pry so, those hospital nurses.

I hadn’t realised that anything could hurt so much, though the price was low if it bought me life.

I complained bitterly about cold feet, and the midwife let me keep on my long woollen socks. But I didn’t know that there would be so much mess, so much blood. It got everywhere, even on my socks, and before I realised what was happening she had stripped them off.

The midwife stared at my disability in horror and disgust. There was no point in the story about the accident.

‘Please,’ I begged her between contractions. ‘Don’t tell. Who will take care of my baby?’

She threw me another pair of socks. ‘I don’t know you!’ she cried.

She ran outside, hand over her mouth, and I heard her retching in the garden. Then the gate banged and I was alone.

There was more pain, but I don’t remember it very well, and eventually my beautiful baby emerged. The child that will save me. Her grip is very strong, my lovely baby. She is pink, healthy, flushed with new life.

She is the image of me too — petite, fine-boned, thick dark hair. Even to the twisted little left foot and the extra little toe.

*

I flee out into the night, the mud and the rain. The gate clangs behind me like the doors of hell. Which of my choices is the least hideous? Her life? My life? Without her I might continue in my drab existence, since the letter about my physical has never come. But I never dare try for anything better, for that would require the physical.

Walking is agony. It feels like I am torn down there. A bus comes along and I flag it down, and sit up the back in the empty dark. My baby is crying softly. I brush the raindrops off her cheek and put her mouth to my breast. She sniffs around for a moment then latches onto the nipple with such force that I am hard put not to cry out. What life there is in her, my lovely darling.

What can I offer her? No more than my mother could give me. Go to some place so backward that they don’t even bother about the Law, as long as you are careful. Give up the little I have, in exchange for nothing for either of us!

Cut off the evil toe, break the bones and twist them into shape, hoping that I can do better than I was done to. Give her a lifetime of pain and fear and endless tedium, until the inevitable physical exposes her.

Or stay in Sydney? All newborn must have the physical. The same result, only sooner — termination.

*

The bus has come to the end of the line.

I get up, leaving blood on the seat. Wipe it off with my hand. I walk up the curves of the road, street lights gleaming on wet bitumen. She is warm in my arms.

Now the sea roars far below. My steps have brought me to The Gap, a fitting place. People in despair have sometimes found the answer here.

The moon comes out, shining on the welcoming rocks. Temptress!

My baby whimpers and I give her the breast. What kind of a life can there be for her? Should I just leave her to fate? Here? By the cliff? The easy way out?

Maybe if we were to go together. Life isn’t worth this pain.

How eagerly she sucks. How she wants to live. I thought she would save me. I didn’t realise my duty to her.

I pull her off the breast, her mouth making a little wet plop. I stand on the precipice, holding her away from me. Her life, my life. Our lives. The waves cry out for a sacrifice. The glossy rocks beckon. They know there is only one solution.

My baby opens her eyes and stares up at me. She knows too. She is loyal.

I am just as loyal. I will do what’s best for her, whatever the cost.

*

The wind is cold on my abandoned breast. It is blowing right into my heart. Why didn’t I give her a name?

*

Last night was the coldest I have ever been. Where are my mother’s arms? Where are my lover’s arms? Where is my babe-in-arms? All gone.

*

A letter came from the Medical Inspector’s Office today. I haven’t bothered to open it.

Such a decent world.

2: Fugitive

I don’t deserve to live.

*

I raised my head. I must have lain there all night, for a glass of milk had gone thick as yoghurt. My tea cup had a series of brown rings inside. I gulped what was left, drowned insects and all.

The fatal letter lay on the floor. The yellow envelope. I crawled over to it, staring at my name through its window.

Aislyn Athanor

62/12 Paradise Gardens

What a joke! I live in the ugliest suburb in the whole of Sydney, and Paradise Gardens is a cruel hoax. It is a cement rendered monstrosity built in the middle of the 20th Century. The ceilings are low, the stairways dark and stinking, the outside walls festering with concrete cancer. My one-room flat is the saddest hovel in the whole building.

I reached for the letter. It crumpled in my hand. I could not bring myself to open it. I lay on the floor again. My lost baby. My dear love. Murderer! Monster!

No, I felt her say. You did what was best, for both of us.

‘I did it for myself!’ I screamed. ‘I want to die too.’ I imagined running all the way to the Medical Inspector’s Office and exposing my disability in the foyer. The guilt was unbearable.

I want you to live, she sighed in my head. Open the letter.

I opened the letter.

Office of the Medical Inspectorate

32nd Floor

The Millennium Tower

April 21 2026

Aislyn Athanor

62/12 Paradise Gardens

Dear Aislyn Athanor

Be advised that your Citizen’s Card will expire in seven days. You are hereby required to present yourself to the Assessments Office, 38th Floor, on April 26, for your Physical Examination, or to any regional office should you be unavoidably outside the city at that time.

Be warned that, under Section 31 (b), Subsection 19, Clause (e) of the Regulations to the Maintenance of Genetic Quality (Human) Act, 2006, (also known as the Genes Act) the Office is authorised to implement penalties, without trial, for breaches of the Act. Such penalties may, at the discretion of the Chief Medical Inspector, include fines, temporary deprivation of Citizen’s Card, permanent loss of Citizen’s Card, incarceration for periods up to life and, in the case of irretrievable genetic degradation, mandatory termination.

I remain

Your servant

Margaret Mulcted, MB BS Ph D (Human Genomes) Ph D (Biotech. Eng) M Publ. Admin.

Chief Medical Inspector

I dropped the letter, which fluttered to the floor, then snatched it up again. April 26! What was today’s date? I had no idea. Time had curled up into a ball over the past weeks. I couldn’t unravel it.

I pressed the button on the front of the NetScreen. It stayed dark. The power must be off again. I checked the box on the wall. The circuit breaker said ON.

They have ways of checking up on people. Maybe when the screen is off it’s watching me. The sudden panic felt like hands around my throat.

I couldn’t stay here, but where could I go? I had no friends, no relatives. Nobody cared if I lived or died.

My flat exposed the poverty of my existence. One chair, one fake wood table, one ragged mattress on the floor. One cup, one plate, one knife, fork and spoon. A cardboard box of second-hand clothes. Brush, toothbrush, caustic soap. But without this room I would be at the mercy of every thug and vagabond on the streets.

To stay meant to die, my daughter’s sacrifice for nothing. I slipped on the gold-plated chain my lover had given me. It was the cheapest of jewelry, the gold already wearing off in places, but I was sentimental about it. In my shoulder bag I packed a clean blouse, skirt, socks and knickers.

I have no bathroom. I stood in the sink to wash myself, then threw the bloodstained jeans and knickers in the corner. I dressed in my best, put on my only pair of boots, counted the money in my purse, thirty-one dollars, and abandoned my home.

I went randomly through the decaying streets. I had nowhere to go. I walked and walked, in the gentle rain. I didn’t care. I was a monster who deserved punishment. My breasts were so full of milk I thought they were going to burst. I hadn’t thought about that problem.

Going past a newsagent, I saw the date. April 25. I had until tomorrow. I thought about fleeing to the country, as my mother had done. There must be places to hide. But I could not. I owed it to my daughter to make something of my life.

That was another joke. If I did not turn up for the physical, my Citizen’s Card would be cancelled and a warrant would be on the Net within hours.

*

It was mid-afternoon and I had nowhere to sleep. My breasts hurt, my ankle too. I had not walked so long in all my life.

Limping under an iron bridge, high in a crevice I glimpsed someone staring at me, a shape living in a cardboard box. Would I be that lucky tonight? The NetScreen was full of propaganda about cardless people. Their life was brutal and brief, on the Screen.

I hurried away, thinking of my lover that I had spurned so cruelly. I had not spoken to him since I knew I was pregnant …

Swimming in those memories, I realised that I was outside his block of flats. Dare I ask him for help? My rejection had hurt him terribly. The shy boy had become an angry delinquent, then he’d disappeared from the packing factory, taking to petty crime and hanging around with street toughs.

I pressed the button for his apartment. After a long time a woman’s voice screamed, ‘Who is it?’ I almost gave up. No trace of kindness there.

‘Aislyn. May I speak to Jeffie, please?’

‘Jeffie!’ I heard her bellow. She must still have her finger on the button. ‘It’s that little slag from the box factory. Tell her to clear out!’

He came to the speaker. ‘What do you want, Aislyn?’ That hurt, though I knew I deserved it.

‘I need help. Can I … talk to you?’

The speaker went dead. I wanted to run away. I almost did. Then he was back, his voice distorted to a tinny whine.

‘Come up, but one minute only.’ He was still angry. Why wouldn’t he be?

I dragged myself up the stairs, lurching like the cripple I was. I pressed the button of his door. He jerked it open. The woman stood a couple of steps behind him, a big, red-faced trull about fifteen years older than he was. I imagined them in each other’s arms. I had to push the image away.

‘I need help, Jeffie,’ I whispered.

‘What’s she saying?’ the woman cried, trying to get past.

He held his arm out, blocking her way.

‘What’s the matter, Aislyn?’

‘I can’t … can we speak privately, Jeffie?’

‘No!’ he said roughly.

I turned away. All along I’d known it would be no use.

‘Hey!’ he said when I was at the top of the stairs.

I turned. He came outside, shutting the door in the woman’s face. ‘I heard you were pregnant.’ I saw some yearning in his eyes. He eyed my flat stomach, my distended breasts. ‘Is it mine?’

‘It was,’ I said.

‘Wasn’t I good enough for you? Would you rather our baby had no father, than me?’ There were tears in his eyes. Ah, how he wanted that baby.

‘I didn’t have a permit,’ I said, unable to face him. Then I lied. ‘I wanted to spare you that trouble.’

‘I didn’t ask you to! Where is my baby?’

I felt a surge and realised that the milk was flooding out, wetting my blouse.

‘She died, yesterday.’ My face had frozen like stone. ‘She only lived for a few hours.’

He stared at the spreading circles. Abruptly he threw his arms around me. ‘Aislyn, my love. Come inside. You must be—’

I couldn’t bear it, after what I had done to him, and to his daughter. I pushed him away. ‘I’m so sore,’ I said, but it could never be excuse enough.

We faced each other. The door wrenched open and the red-faced woman stood there, her hands on her hips. She read me in a single glance. ‘Get rid of her!’ she hissed.

‘You’d better go,’ Jeffie said.

‘Don’t come here again!’ the red-faced woman snapped.

I stumbled down the steps. I couldn’t blame him. There was none left after I’d finished with myself. If he really knew what I’d done …

*

On the streets the simplest things in life are incredibly difficult. Like washing. A few trips to the laundromat would exhaust my thirty-one dollars. Besides, everyone knew that such places were watched.

Every time I thought about the baby my breasts leaked. In a few hours I stank of sour milk. I washed my blouse in rainwater leaking from a bridge, but had to put it back on wet. Someone would steal it if I left it anywhere to dry. Before it was, I stank of milk again.

I bought the cheapest food I could find — a tin of condensed soup and a bag of carrots. I ate the soup cold, sitting under a concrete overpass, and knew that someone was watching me. I hurried on, always looking over my shoulder. It was nearly dark now. My ankle was giving out. I had to find somewhere safe to sleep.

I climbed through a fence, across railway tracks and caught sight of a partly overgrown tunnel abandoned years ago. I hobbled towards it. As I stood at the entrance, peering into the darkness, a woman stepped out in front of me. I jumped, for she was a good head taller, with shoulders as broad as any man’s. She folded brawny arms across her chest, waiting for me to speak.

‘I need somewhere to sleep,’ I said.

‘Find your own! We’re full.’

‘Please,’ I squeaked. I felt so small and insignificant.

She considered, or pretended to. ‘Twenty dollars for the night.’

‘Twenty!’ In my desperation I considered paying it. As I put my hand in my pocket, dark shapes moved in the tunnel behind her. If I went in there I wouldn’t come out again. There were worse things than the medical examination.

‘I don’t have it,’ I said, and turned away. I still had twenty-six dollars, as it happened. How long would that last, even if I slept for nothing? Less than a week.

Along a bit I came to an ancient railway bridge, supported underneath by a series of small arches built of iron. Distant street lamps emitted a feeble light. Between the arches I saw metal-clad valleys large enough to sleep in, if I could get up there.

It was a hard climb in the dark, and every surface was wet. I used to be afraid of heights, but not any more. Not after The Gap. It didn’t matter if I fell.

At the top I found a space between rusty iron beams. I pulled myself into it with a sigh of relief. Something glinted in the darkness in front of me. It moved and the street light caught a shining edge — a large knife. A pair of eyes appeared behind it.

‘I’m going!’ I ran along the girders in the darkness.

The second and third valleys were also occupied, the latter by a gaunt old man. I stood in front of him with my bag hanging from my hand.

‘Isn’t there anywhere?’ I cried.

‘Last one’s free.’ He spoke in a whispery croak. Then he laughed. ‘Free now, all right.’

Approaching the fourth, cautiously, I heard a baby crying. It set off a deluge of milk down my front. A man’s voice tried to calm it.

‘Where’s mummy?’ a child’s voice said fretfully.

‘She’s … gone away,’ said the man. He choked into silence.

I hurried on. Before I got to the last space I realised why it was unoccupied. It smelled awful — really disgusting. I had to ignore it. I couldn’t start again. I wedged myself into the entrance, where there was a bit of a breeze, and ate a carrot. I pillowed my head on my bag, did my best to block out the odour and tried to sleep.

It was an evil, haunted night. My poor little baby. I keep seeing her face as I held her out in front of me. Her wide eyes, so helpless.

I can’t bear to write about her.

*

It must have been nearly dawn when I got to sleep, but I did not sleep long. I was woken by an absolutely nauseating stench. The sun was out, shining directly down the iron valley, illuminating what I had been sleeping with. At the far end was the corpse of a middle aged man with a needle still stuck in his arm.

I went back to Jeffie’s place. It was eight in the morning by the time I got there. The time of my medical examination. I supposed I had a few hours before the warrant would go on the net.

I watched from across the street. In an hour or so the red-faced woman went out, dressed like an abattoir worker. I ran across the street and pressed the button for Jeffie’s apartment. He answered at once.

‘It’s Aislyn,’ I said.

‘Go away!’

‘Please, Jeffie. Please help me. You’re all I have in the world.’

‘Then you’ve got no one!’ he choked, but I heard the lock click. ‘Aargh! Come up.’

I undid two buttons of my blouse. I felt awful but I had no option. I’m not much to look at, but surely more than that hard-faced cow he lived with.

He ushered me inside as if afraid someone would see me. I had to convince him quickly. ‘I didn’t turn up for my Medical Examination.’

His face was unreadable. I leaned forward. His eyes slid down to my chest.

‘Why not?’

I hesitated. ‘I’m afraid.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with you, is there?’

‘No, but my mother was … scared of the test. She had some kind of secret. I’m frightened.’

‘Don’t be stupid!’ he said. ‘Just make another appointment.’

‘I’m really frightened.’

‘What do you want from me?’

‘You know people. I want the name of a doctor I can trust.’

He looked at me suspiciously. ‘You can’t trust anyone, you know that. Not even me!’

‘Just a name,’ I begged.

‘I’ll ask.’ I knew he wouldn’t. He was looking out the window. He just wanted to get rid of me.

*

I walked all day, fed myself on condensed soup and raw carrot, and brooded. What was the point to my life? I would be better off dead. My mother should have done to me what I did to my daughter.

I cut across the old railway yards and the abandoned technology park. Crossing an elevated footbridge towards the University, I caught sight of the gleaming brass and wires of the Centre where my mother had worked. It was one of the few buildings that did not look run down.

I thought of her, hiding in that decaying shack up the north coast, grieving for all she had lost. Cyssa had been a brilliant researcher in Cultural Bio-Engineering. She had been working on the design of future societies, until I destroyed her life.

A hopeless longing woke in me, to finish her work, to design the perfect world. It was the only way to repay her, and perhaps atone for my terrible crime. I wanted to, more than anything, though I knew it was a dream.

3: Corrupt Flesh

I hauled myself up to my hideout in the bridge, trying not to think about the dead man. I didn’t think I could stand another night.

I went past the other valleys, ignoring the occupants as they ignored me. All but the second last, where the little baby was whimpering. The father was trying to spoon tinned soup into it, without success. Once more I flooded everywhere.

‘It’s that funny lady again,’ said a small girl’s voice.

I went red but the man did not look up. I hurried by. Back at my own sleeping place I hesitated, and the longer I stood there the more I knew that I could not go in. After a day in the sun, the heat and the flies …

I retched over the side, and was tempted to leap after it. I had lost the will to run. I was a monster. Society was right to purge me, to make sure I did not pass on my corrupted genes.

I headed back the other way. The baby was still crying. In front of the little family group I stopped. The man’s face was tortured.

‘I don’t know what to do!’ he cried.

I stood there, looking down at the baby and the desperate father, and felt the milk running down my belly.

‘I do,’ I said, and unbuttoned my blouse.

*

You can’t imagine the conflicts I felt, squatting there in that metal gully with the rusty iron criss-crossing above me. I was still sore from giving birth. The baby pulled at my breast. The two children stared at me as if I had dropped from the sky. The father’s eyes kept sliding towards me then, when he realised, flicking away again.

I felt useful for the first time in my life. But I knew a terrible sadness, that the child was not my own. Tomorrow I would be gone and never see it again. My baby either.

‘It’s rude to stare, kids,’ he said, but they were incapable of hearing him. ‘My name is Ben,’ he said softly. He was handsome, with broad shoulders. He had a very soft voice, and curly brown hair, and deep blue eyes. His voice was what I most remembered, after. There were no lights or shadows in it, so it was hard to distinguish the words, but it seemed kind.

‘I’m Aislyn.’ I put out my hand. I immediately felt embarrassed, shaking hands while his baby sucked at my breast.

He did not look down. He had a face that must have been comfortable with laughter once. There was something hiding in those brown eyes now.

‘Clara, Tom, shake hands with Aislyn.’

The children did so, very gravely. I leaned back against the metal and closed my eyes. ‘I’m so tired,’ I said. I wasn’t but I had to block them out, disconnect them from me. Coming to terms with the baby, where mine should be, took all the emotional energy I had.

The child must have been starving, the way it pulled at me. Oh, my lost little love. I felt hot tears swelling under my eyelids.

‘She’s called Kirrily,’ said Ben.

‘Why is the lady crying?’ piped the girl.

‘Hush!’ said the father.

‘She’s not as pretty as mummy, is she?’

‘Clara!’ hissed Ben. ‘You’re being very rude!’

‘Well, she’s not!’ Clara said defiantly.

I opened my eyes and let the tears run out. ‘I’m sure no one is as pretty as your mother, Clara. What’s her name?’

‘Her name is Katia,’ said the father, then his eyes scrunched up, he broke down and wept. Soon Clara and Tom were bawling too.

The baby lifted her head, gave a couple of brief cries in sympathy, burped a mouthful of milk down my front and fell asleep. I nudged her awake and gave her the other breast, mainly to relieve my own discomfort. While she fed I closed my eyes again, trying to block the crying out. Eventually I did and, lulled by the rhythmic action of her mouth, drifted off to sleep.

*

It was much later when I woke. It was dark and the moon well up the sky. I was woken, I should say, by the father taking the baby out of my arms and placing it in a cardboard box lined with a blanket. The children were asleep in their own blankets.

‘Thank you,’ Ben whispered. ‘She was starving. I couldn’t get any formula.’

I couldn’t think of anything to say.

‘Would you like something to eat?’ he said.

I nodded then realised that he wouldn’t see it in the darkness. ‘Yes, please!’

Ben spooned something out of a tin onto rough chunks of bread and passed the plate across. ‘It’s tinned beans!’

‘Sounds wonderful!’ I ate it bean by bean, making it last.

We sat in silence. He must have been wondering about me, as I was about him, but he did not ask. Perhaps that was the etiquette of life on the streets.

‘What happened to their mother?’ I asked after a long interval.

He turned his head and the moonlight caught one eye, a liquid flash. I knew he wanted to trust me, because I had fed his baby. He shifted on his perch.

‘You don’t have to tell me your business,’ I said. I felt a desperate urge to confess. ‘But I’ll tell you mine. I’m hiding from the Medical Inspector. I wasn’t game to have my physical.’

He let out his breath in a whoosh. ‘They took blood when Katia was having the baby. They said everything was all right. It was, with the other two. But two weeks later they came for her. Last Friday. Bad genes! She sent me a message over the net, to run with the children.’

‘Can’t you get a lawyer?’

He laughed mirthlessly. ‘Not for this! I’m terrified. What if Katia does have bad genes? They’ll take the kids as well.’

‘I think I have bad genes too,’ I said. ‘Is she still alive?’

‘I don’t know. Term— the process used to take months, but the new government has changed the law. I’ve heard they sometimes terminate without allowing any appeal. I’ve tried everything! My uncle, Sam, is an army general, but even he can’t do anything. What can I do?’

Nothing! I thought. There’s nothing anyone can do, not once they’ve got you.

*

The poor man went out in the morning with his children. In the afternoon he came back, looking more tormented. I limped over to Jeffie’s apartment, but he wouldn’t talk to me — the woman always answered the bell, and after the second time she cursed me over the speaker.

‘Come back again, you little slag, and I’ll report you to the Medical Office!’

She must have, for the next day, as soon as I turned the corner I saw someone watching from across the street. My only hope was lost.

On the way home I realised that I was looking forward to feeding the baby more than anything in my entire life. Without me it would die. I liked Ben, and the children too, though Clara and Tom were distant and never really accepted me. They needed their mother too much.

Ben and I talked, in the dark, after the children were sleeping. A computer engineer, he was constantly at the keyboard of his PocketBook, trying to find out what had happened to his wife. He routed his enquiries around the world, through dozens of links, to disguise the trail.

‘My mother was good with computers,’ I said wistfully. ‘I wish I was.’

‘I can teach you, if you like. I’d feel better about you feeding my baby then.’

‘But you feed me!’

‘That’s different. I have money, but I can’t buy breast milk.’

We spent half that night working, and every night after. I knew the basics of the net, of course — it was a part of everyone’s lives. But he taught me the engineer’s hidden codes that gave access to secret places, and about mole programs that could burrow into computer systems, and how to find the subversive sites that would be on the net one day and gone the next. He showed me how to link in through networks long forgotten — old signal lines buried beside highways and railway tracks, power reticulation systems that were no longer used but had never been dismanted, forgotten pay TV cables, and other ways no one thought about any more.

I learned fast. I seemed to have my mother’s skill with computers. I knew what he was searching for so desperately — a corrupt doctor, one outside the system who would do a private medical and fake reports for his children. I wanted the same for myself.

One day, after I had been there about three weeks, I came back with a bag of canned food and another of vegetables to find him staring blankly at the rusting steel. The children were playing down the far end of the gully. It hadn’t taken them long to get used to their new home.

‘What’s the matter, Ben?’

He didn’t answer. The PocketBook lay open beside him, its solar cells iridescent in the afternoon light. The screen showed ‘The Stocks’, one of the most popular sites on the net. Below an engraving of a semi-naked woman bent over in a set of medieval stocks were a pair of scrollable lists. One showed names, the other faces in haggard colour.

I typed Katia into the Searcher. The lists spun like the dials of a gambling machine, then froze. Termination List flashed luridly at the top of the screen and a cartoon below right showed a woman being led to a scaffold. In florid prose I read,

Executed today for the crime of genetic pollution, Katia Anders-Lofts (27) flaunted her depravity in the most blatant way. This mincing socialite, who had everything but sneered at the rule of law, led our stalwart investigators in a dance across five states that lasted for three weeks. Like a gangster moll who would stop at nothing to follow her evil pursuits, she left three medical police dead in her wake and another crippled and begging for a hero’s termination. But valiant to the last, Officer Jungers …

‘Every word is a lie!’ Ben whispered violently. ‘She was in hospital for two weeks after the birth, with an infection. They ripped the drip out of her arm and dragged her from her bed.’

The picture was a full length shot of a slender, attractive woman with frosted silver hair and a faraway look in her eye.

My eyes followed the page down. There were several more paragraphs, which read like the most lurid gossip magazines on the net. Below was a blow up of part of Katia’s face, just nose, eyes and ears, as if looking through the horizontal slot of a letter box, or a prison cell.

CLICK RIGHT EYE TO SEE CRIMINAL’S DEATH AGONIES

CLICK LEFT EYE TO VIEW THE BODY

CLICK EITHER EAR TO HEAR HER LAST WORDS

CLICK MOUTH TO LIST HER GENE CRIMES

VISITS TO THIS SITE TODAY 211,843

Nothing could be said. This was beyond words. I took Ben’s hand, sitting beside him as the children played down the back.

‘They’ll be after the kids next,’ he said listlessly.

‘Isn’t there anything you can do? Can’t you change their identities?’

‘No! Those systems are too protected. I’ve only one hope left.’

‘What?’

‘A lead on a rogue doctor who hates the system. If I can find him …’

‘It’s a terrible risk. What if he’s a stooge?’

‘What’s the alternative?’

*

He went downhill quickly after that. Her death sucked the life out of him as a spider sucks outside the inside of a fly. He looked much the same, he cared for his children just as carefully, and he worked on his NetSearch night and day with quiet desperation, but there seemed to be nothing inside. As the days went by, and one fruitless lead followed another, he practically gave up eating.

‘They’re closing in on us,’ he said to me one night. His eyes looked as if they had been rubbed with sandpaper. ‘I want you to go, now.’

‘I’m not going anywhere,’ I said.

‘Please, Aislyn.’

‘I’ve lost one baby, Ben. I can’t lose another.’

‘Will you … look after her, and the kids, if anything happens to me?’

‘I …’ I hesitated. I didn’t want to make promises I couldn’t meet.

‘I know you’ve got no money. Take this!’ He pulled a wad of notes out of his bag and stuffed it into my hand.

‘I can’t take your money,’ I whispered.

‘You’re not. You’re minding it for my children.’

I sat there with the money in my hands. I didn’t know what to do. He went back to the net, taking desperate risks now, staying on line far too long.

*

‘They’re tracing my links!’ he gasped. He broke the connection. His hand was shaking.

‘How can you tell?’

He demonstrated his sentinel programs. ‘I’ve only three safe links left. When they’re gone, we’ve got to run.’

He kept at it. ‘I feel so close,’ he said a while later. Later still, ‘Aislyn, I’ve found it!’

‘What?’

‘The way into the Medical Inspector’s computers.’

‘What are you looking for?’

‘Tiny discrepancies between old files and recent ones. Subtle differences that might indicate people’s records have been falsified.’

‘Surely they check that themselves?’

‘All the time! In fact I wrote the program for them. But I’m using a much more powerful subroutine.’

‘With this little handheld?’

‘It’s the best there is!’ I saw an instant of boyish pride. ‘But their computers are doing all the work. The PocketBook just downloads the results.’

‘How do you know their computers aren’t watching what you’re doing?’

‘I’m pretty sure they’re not. I wrote their system, and checked it only a few months ago.’

*

Ben finally gave up and took the older children for a walk. I sat in the afternoon sun, watching data flow across the screen of the PocketBook. He appeared on the other side of the yard, one child holding each hand. I stood up and waved. As I did, a shiny metallic van drew up, like an armoured car. The doors flew open and half a dozen officers leapt out. They were dressed in red and black. Medical police! My heart crashed in my chest as if they had come for me.

‘Halt!’ cried their captain. Her troops pointed an array of weapons at the children, enough to quell a minor riot.

A helicopter appeared overhead. Another van raced into the yard, braked and skidded sideways across the dirt. It had a satellite dish on the roof and NetNews Live! in huge red letters across each side. A big man got out, already filming. A woman jumped out the other door and thrust a mike at Tom’s face.

Tom screamed. Ben took him in his arms. Clara clung to his other hand. I caught at a girder to stop myself falling down. Ben seemed to be looking right at me. Was it a message?

‘NetNews Live!’ I said urgently to the PocketBook. ‘Channel scan.’

For once the Speech Recogniser worked. The search went into the background. The news came up at once and began scanning through dozens of channels. Ben’s face appeared, filling the screen. He seemed to be looking right into my eyes. ‘Stop scan!’ I said.

‘Any last words, gene traitor?’ the reporter screeched out of the speaker.

Ben closed his eyes and opened them again. ‘We’re ordinary people, just like you,’ he said to the camera.

The chief of police elbowed the reporter out of the way. ‘Where is the baby?’

Ben’s face crumpled. ‘She died, after her mother was taken from the hospital.’ Then he looked up again, as if saying, Here’s your chance. It’s the best I can do. Save yourselves!

‘Liar!’ She rapped orders at her troops. ‘Search the bridge and all around.’

Ben and the children were forced through the back doors of the van. The doors slammed. I saw a shadow behind one of the reflecting windows. There was nothing I could do.

Snapping the PocketBook shut, I thrust it into its bag. I lifted the sleeping baby. Where could I go that they wouldn’t find me? There was nowhere to run to, with the helicopter hovering above. I climbed up the steel framework and across into the next valley.

Down the end, against the stonework of the bridge abutment, there were spaces where someone small might hide. I edged past the corpse, holding my breath. Nothing could block out that smell. I squeezed sideways into the smallest space, Kirrily held out after me. I bumped her head and she began to cry.

I put her on the breast, which took a long while to calm her down. I heard the tramp of police coming along the bridge structure, the rude interrogations, the cries of the cardless hoboes as they were taken away. Boots clattered in the valley next door. Two officers were talking.

‘This is where he hid,’ said one. ‘Must have been here weeks — look at all the empty cans!’

‘Give me your torch. My batteries are flat!’

‘Don’t see no tins of baby formula,’ said the first again, sorting through our rubbish midden. ‘Maybe it did die.’

‘You’re not paid to think! Keep looking!’

‘Hardly call what I get pay,’ grumbled the man at the rubbish pile.

‘Go and check up the end.’

He tramped up towards my hiding place. I held my breath. The footsteps stopped not far away and I heard him gagging.

‘What’s the matter?’ cried the other.

‘A dead man. A needle job!’

‘How dead?’

‘More than you want to know. Weeks! Baby wouldn’t be in here.’

‘Check it anyway.’

His boots came crackling through windblown leaves and papers. Kirrily pulled off me and looked around. Her eyes screwed up. Don’t cry, or we’ll both die! I touched her cheek with my fingertip and she took the breast again.

The guard stopped right at the wall, shining his torch around. I couldn’t breathe. I thought I was going to fall down.

The torchlight disappeared, then came back again. I could hear the man’s heavy breathing, even see the hand holding the torch. I forced myself further into my crevice. A sharp piece of metal dug into my back. The baby pulled off and again its eyes screwed up. It took a long inward breath, prelude to a scream. I put my hand over its mouth.

The light went away. The man called out, ‘Nothing here!’ and headed back up the other end.

‘You sure?’ said the other, apparently staying outside.

‘I know what my life is worth!’

The footsteps headed off. I took my hand away and stroked Kirrily’s head. She gave a little cry and went back to feeding.

In the confined space the smell was awful, but I stayed where I was. I didn’t trust them to be gone. My knees would hardly hold me up. Finally, after the baby slept, I opened the PocketBook one-handed and checked NetNews. It showed the officers forcing the last vagrant into the custody van. The cameraman took lingering close-ups of Ben and the children through the back doors. The doors slammed shut. The van drove off. The NetNews van followed it, still filming.

I never saw Ben or the children again. A week later their termination notices appeared on the net.

*

In the night I went back to our valley. It felt so empty now. I ate a tin of something, I don’t know what, and put the baby to bed in its cardboard box. In the middle of the night I realised that the PocketBook was still on. I was about to shut it down to preserve the solar charge when I saw an alert flashing in the background.

I panicked. They must have traced Ben’s link. But I touched the search window and there it was, the result of the search.

Dr Rogerio Crandy

44th Floor

The Millennium Tower

There was also a suburban address where he had his private consulting rooms. I memorised them both and closed the program.

DELETE ALL LINKS? The PocketBook asked.

‘Yes!’ I said aloud.

DELETE ALL TRACERS?

I deleted everything except Ben’s programs. I don’t know why I kept them. I could never have reproduced his search by myself.

I sat there for the rest of the night, just staring out into the darkness. A day earlier and we would all have had a chance. Now it was just me and the baby.

4: The Holy Grail

It took a month to get an appointment with Dr Crandy, who turned out to be a senior advisor in the Medical Inspector’s Office. He also had a practice doing reconstructive surgery for people mutilated in accidents.

His consulting room was in a dingy building in the western suburbs. That didn’t surprise me. All doctors seemed to have dingy offices. He had no receptionist. That did surprise me. He didn’t ask to see my Citizen’s Card. I felt a trickle of hope.

‘What can I do for you …?’

I had no energy to approach the matter obliquely. ‘Fix my foot!’ I took off my boot and sock, and held my breath.

He felt my thickened ankle and the twisted bones of my foot. It took less than a minute. His fingers were extremely cold. He took off the other boot.

‘Hmn! Quite attractive, as feet go!’ His fingers lingered on my toes. ‘You have a genetic deformity which has been further mutilated.’

‘My mother tried to make it better.’

‘You realise that you are asking me to commit an illegal act, for which the penalty is termination?’

‘I do,’ I said. ‘Can you repair it?’

‘Of course.’ His black eyes probed me. ‘As long as you’re prepared to pay my price.’

‘I don’t have a lot of money.’

‘I wasn’t thinking of money.’

*

The first part was not painful. He scanned both feet in a body imager and made 3-D computer models of their anatomy. Then he reversed the model of the good foot and superimposed it on the other. That showed him where to cut, where to build, where to manipulate and restructure.

The second part was very painful. I won’t go into the details. He took my crippled foot apart, dissected it into its components of bone, muscle, tendon, sinew, blood vessel, nerve network and skin. He reshaped the bones and the joints using laser ablation, regrew the bone and joint surfaces, then put down formwork of an internally dissolving plastic to which the individual components of my foot were attached. The different tissues grew in their proper positions on the formwork. It took quite a while. Many weeks.

The price I paid I shall also draw a veil over. Suffice it to say that the man was a deviant and a pervert, though a harmless one. I was glad to pay what he wanted to save my life and Kirrily’s. It was a contract freely entered into. I liked him, in spite of … all that.

Six weeks later I stood up on a new foot that was the mirror image of the good one. It didn’t hurt at all, though it felt a little strange to walk on. He’d told me to expect that, at first. I also had a Citizen’s Card in my pocket, which meant he’d faked my gene test results. I don’t know how. I didn’t ask.

‘Why do you risk your position and your life for people like me?’ I wondered. ‘Apart from …?’

‘Because I hate the whole rotten system!’ he said vehemently. ‘The Genes Act must be undone. It’s what people are that matters, not what they look like.’

I was shocked. It was the first time I’d ever heard someone speak openly against the system. My mother never had, nor Jeffie. Not even Ben.

‘Oh!’ I said.

He took me by the shoulders. His grip was painful. ‘Now you listen to me, little Aislyn. I know who you are!’

‘What do you want?’ I stammered, thinking that he intended to blackmail me.

‘Aislyn Athanor, daughter of the brilliant Cyssa Athanor! You’re smart, Aislyn. We need people like you.’

‘I didn’t even finish high school,’ I said weakly.

‘I’ve seen your test results. You could be anything you wanted.’

For a moment I saw the University on the hill, the lovely old sandstone buildings, the jacaranda tree. Perhaps it was possible. The baby whimpered and reality intervened. ‘I don’t have the money.’

‘What about your mother’s estate?’

‘I wasn’t aware that there was one. I was afraid to ask.’

‘I checked your file last night. She wasn’t poor. There’s an apartment in the city and an old house up the north coast. Money has accumulated from rent since she died, and dividends from a portfolio of shares. It’s no fortune, but enough to keep you while you study. Go off and learn, and when you’re ready, contact us.’

*

With a full Citizen’s Card, and money in the bank, my life was transformed. I set out to take up the opportunities I’d never had. Yet I could not stop thinking about what he’d said. Using the PocketBook, I visited several of those subversive sites on the net, and for the first time I began to question the fundamentals of the society I lived in.

But my own holy grail always came first — to complete my mother’s work. It was hard, with Kirrily completely dependent on me, though I never thought of it that way. It was what I’d always wanted. In a year I had finished high school. Four years later I had a combined degree in Ethics, Socio-Biology, Database Mining and Genetic Engineering, with the highest honours. Three years after that I was awarded a doctorate in Cultural Bio-Engineering from my mother’s Centre.

A week later I was hand-delivered a letter from the Centre.

Dear Dr Athanor

I have great pleasure in offering you the position of Researcher in Cultural Bio-Engineering at the Centre. We have watched your career, and reviewed your research, very carefully, and the Committee was unanimous in selecting you.

As you know, the University is going through a period of great financial stringency. Nonetheless, we are able to make substantial research funds available, should you wish to complete the work your mother began so long ago. Be assured that this research is considered to be of national importance and has support at the highest level.

We await your decision with the keenest anticipation.

Prof. Eolie Chalmys

Head, Centre for Advanced Bio-Engineering

Words can’t describe how I felt when I opened the door of the room that had been my mother’s office twenty eight years ago, and sat down at her desk.

I had read her scientific papers a hundred times, and now set out to complete my mother’s dream, to design the perfect society. It was exciting work, but before I had gone very far I began to encounter mysterious gaps in her research. It was as if vital studies had been lost. I searched every library in the country but couldn’t find anything.

Obsessed with my research, and spending what little free time I had with Kirrily, I had hardly noticed what was going on in the world. Oh, there were occasional disappearances from the University, but none that affected me. I kept to myself — a hangover from my previous existence, I suppose.

A few months after my graduation I was sitting with Kirrily watching the NetNews. In my eight years of study I’d not allowed myself the luxury of idly watching the net.

The President, a big, strikingly good looking man, came on the news. He was always there these days, dispensing paternalistic pap. NetNews was a more important forum than Parliament had ever been. His fashion-model wife stood beside him, as always. They personified the cult of beauty that dominated our times.

I vaguely recalled a long struggle between an incompetent Prime Minister and the elected President, a charismatic former footballer. The President won and his puppet government rubber-stamped changes to the Constitution. The President was speaking now. I turned up the volume.

‘This recession, or should I say depression, has not come about by accident, or even through the incompetent policies of the previous government. There is a secret force operating in Australia, one that has set out to pull our great country down. A coalition of failures who cannot bear the success of others, and prefer to drag everyone into their gutter. They are born to failure. The nation must be rid of these parasites!’

He might have been talking about the opposition, though I had a feeling he wasn’t. I felt that there was something hidden in his words. I flicked to another channel, where a panel of economists were disagreeing about the recession.

‘They took my teacher today,’ said my daughter. I thought of Kirrily as my daughter. She was just nine, a slender, pixie-like girl with silvery blond, wavy hair.

‘Who took your teacher?’ I asked idly, my mind still on the news.

‘The Board took her. She was too fat!’

I shot up in my chair. ‘What do you mean, too fat?’

Kirrily was quite matter of fact, the way kids that age are. ‘You know how they take people who’ve got something wrong with them?’

‘I know,’ I said.

‘Fat people are bad. They dirty our genes! So the Board takes them away.’ She changed to a wildlife channel.

I couldn’t concentrate now. I went out into the kitchen and opened up Ben’s battered old PocketBook. I’d not used it in months and the batteries were flat, but the overhead light brought a trickle of current from the solar cells.

Opening a file, I began tabulating population statistics for a paper I was writing. As I did so, I noticed significant falls in the population of certain age groups since the previous census ten years earlier.

It had to be a mistake. But it wasn’t. The population of over-65’s had dropped, when it should have risen significantly. There were smaller declines in younger age groups. Overall, the loss represented nearly two hundred thousand people!

‘GoverNet, Medical Inspector’s Office, genetic crimes list,’ I said urgently to the PocketBook. Being a secure site, it asked for a password. I gave it, twice, but it wouldn’t let me in. I was so furious that I did something really stupid. I called up one of Ben’s mole programs and set it to work. The site opened. Under Termination Categories, which had once only been for “irretrievable genetic degradation,” the list now stretched off the bottom of the screen.

Other crimes included obesity, ugliness (as defined), IQ below 70 points, dementia and a dozen other ailments, incurable stammering … I flicked to the Termination List on NetNews. I hadn’t looked at it in years, at which time it had only contained a few names per day. There were dozens on today’s list.

I closed the lid. It was as if the lights had gone on after 28 years of darkness. I remembered my first year Ethics classes. I had to do something. What had my doctor’s name been? Rogerio Crandy. I opened the Directory and was about to speak his name into the Searcher when a lifelong habit of caution prevailed. Instead I chose List-Alphabetical, and scrolled through the CRA’s to Crandy.

Two names were listed but neither was his. He was not on the doctor’s or the specialists’s lists either. Well, I’d last seen him more than eight years ago. He could have died. He might have gone overseas, though few did in these days of isolationism and world recession.

*

A few days later I turned on the news and there was his face, heading the bulletin.

‘In a special edition tonight, we report on the suicide in custody of notorious pervert and gene criminal Dr Rogerio Crandy. Dr Crandy was to face trial charged with illegal surgery, falsification of computer records, issuance of false identities, tampering with scientific samples and concealing genetic degradation. Due to the destruction of both his offices by fire the full extent of his perfidy may never be known …’

I fumbled out my Citizen’s Card to see if his signature was anywhere on it, but it wasn’t. It did not make me feel much better. I am by no means ugly, certainly not fat, but I stand five feet nothing in my bare feet (fifty years after metrication and we still measure height in feet). Maybe short people would be next.

Surely not me! I thought. My research has support at the highest level. It occurred to me to wonder what that meant. My very tangential inquiries elicited that it meant exactly what it said.

5: The View from the Top

The first we knew of the disease was on NetNews, of course.

A man was staggering down George Street with blood running out his mouth and nose. His arms were mottled with purple bruises. He collapsed, while the cameras dwelt lovingly on his affliction and his agony. I sat up. NetNews desensitised one to almost anything, but this was something I had not seen before.

Or had I? Cutting the news, I called up Diagnostic® and opened the SymptomSeeker. I typed in what I had seen. It came up with nothing. Bloody useless program!

I linked to the WHO site in Geneva. All lines are busy! I tried the US Centre for Disease Control in Atlanta. It took ages to get through. I linked the SymptomSeeker to the CDC’s database. Again, what normally would have happened instantly took minutes. I split the screen and went back to the news item, updating my file with other observable symptoms. After a few minutes two words flashed into the window.

HAEMORRHAGIC FEVER.

There were a number of these but I found a match just as the reporter did his piece to camera and told me.

EBOLA VIRUS.

Ebola had originated in central Africa, killed a few hundred people there in a number of outbreaks between the 1970’s and the 1990’s, then vanished again. It had gained a lot of media attention, more because of the gruesome nature of the deaths it caused than for any widespread threat. Most people who caught it died, but because it had disappeared no one had done any work on a vaccine.

I turned up the volume. ‘They’re calling this disease the Ebola flu,’ said the reporter, ‘because it’s easily spread by coughing or kissing. Or sex!’ He gave a false laugh. ‘Take care who you go to bed with tonight, folks. I certainly will be!’

I knew it was nothing like the flu virus, of course. But it must have mutated, to be transmitted in the air that way.

*

The next day I was called into the Director’s office. Prof. Chalmys, a woman of about 60 years, sat behind a huge tungsten desk with absolutely nothing on it. Her face was as tight as a ballon from the latest in cosmetic skin regeneration. It didn’t match the rest of her. One corner was occupied by her computer, a squat black cube. The screen, on a swing arm by her desk, was unlit.

‘I want you to head a special task force into the virus,’ she said. ‘You will have the status, and remuneration, of a Head of Department, and a research budget limited only by your ability to spend it. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.’

I didn’t know what to say. It was too much a dream. I’d never liked the Director, who had the habit of looking half a metre to my right instead of at me. Moreover, she was well known to be obsessively secretive, a blame-shifter and a credit-taker. I wondered why the job was being offered to someone as junior as me. On the other hand, my work had been pretty good so far. It was a fabulous opportunity.

‘I would be honoured,’ I said, ‘as long as I’m given access to everything I need.’

‘Is there anything in particular you require?’ she asked coolly.

‘I’ll mail you a list.’ What I really wanted was the rest of my mother’s work. She had to have written more than I’d found.

I was given everything I asked for, including my mother’s missing research papers. However they said so little that I wondered if she had been losing her mind. Then I realised that they had been tampered with. I knew her writing style so well that the deletions, and the alterations, were obvious. Why? I kept asking myself. What was being covered up?

And then again, why choose me? Was the investigation just a sop to the politicians? Was I being set up to fail because I was so junior that I didn’t matter?

*

Ebola flu spread across Sydney, then Australia, like an atomic detonation. Within a fortnight a hundred thousand people had it. Within another fortnight, 76,000 of them were dead. It was more virulent than it had been thirty years ago. I suspected that our purified gene pool lacked immunity. Australia was put under international quarantine.

How had it come about? That was the question no one could answer. How had a virus that had seldom been reported outside Central Africa, that had not been heard of for more than 30 years, suddenly appeared in the centre of Sydney?

A few days later I received a personal call in my office. Kirrily’s school had been closed. The husband of a teacher’s aide had come down with the fever. The aide was not on any of Kirrily’s classes, but I was still afraid.

I left the office instantly and picked her up. No one at the school had come down with the disease, and Kirrily had no symptoms either.

That night I sat up late, watching the progress of the virus. The Case-Fatality Rate was now 79%. 79% of people who got the disease died.

I ran into Kirrily’s bedroom in a panic. She was sleeping, holding a long-eared rabbit across her chest, a fluffy toy she carried everywhere with her. I knelt by her bed, watching her as she slept. You’re all I have in the world, Kirrily. I’ve lost my mother, and my daughter, and suddenly my work doesn’t seem as important as I thought it was. I can’t lose you too. I loved her obsessively, though I tried not to show that.

I ran back out again and logged into the Health Department site to check some medical statistics.

Age group of concern? it flashed.

I typed in — 7-10.

Attack rate, weekly per hundred thousand — 4400.

Case fatality rate — 86%.

Kids were more at risk than adults. No surprise there. They usually were, especially if they had no genetic resistance. If the resistant genes had already been culled from the population.

We had to get away. I ran around the apartment, throwing clothes into suitcases. My job gave me pause, but only for a moment. My suspicions had hardened. I was being used and maybe my mother had been too. Damn them!

Where could we go? Home! It just popped into my head. We’re going up the north coast. We’ll be safer there, if there is anywhere safe in the world.

I made ten trips to the garage, staggering under stuffed suitcases, boxes of food, matches, torch batteries and all the other things we’d need for a stay that might run into months.

‘Wake up!’ I said, shaking Kirrily by the shoulder.

She looked up at me sleepily, rolled over and went back to sleep. I shook her awake. ‘Get up, Kirrily. We’re going on a holiday.’

‘Mmm,’ she mumbled.

‘To the country,’ I said. ‘You’ll see rabbits, kangaroos, wombats, frogs …’

She woke up at once. ‘I love frogs.’

‘Well, there’s lots where we’re going.’

I led her down to the car, then ran back to lock up. I was just closing the door when I remembered Ben’s old PocketBook. I didn’t suppose it would work where we were going. I took it anyway, for sentimental reasons.

It was pitch dark as I backed the car out onto the street. A full moon made the city more silent and statue-like than I had ever seen it. It looked like one of those Future Gothic places you see in space operas.

Only three blocks away I saw my first live victim — though ‘live’ was, in this case, an overstatement. A middle aged woman lay sprawled in the middle of the road, a dark puddle beside her. I pulled up next to her but it was quite obvious she was dead. Ebola flu is a horrible way to die.

I sped on, and saw many more bodies that night. Kirrily did not, fortunately. She went back to sleep as soon as we were in the car, and slept the night away.

I came around a corner, driving too fast, and saw a roadblock directly in front of me. I skidded to a stop with the bumper touching the barrier. The officer tapped on the window with the butt of his torch. I opened it, trying to control myself. In a lifetime I would never get over the fear of people in uniforms.

‘There’s a curfew, lady.’

‘I’m on official business,’ I said. I showed my Citizen’s Card and my Centre Pass.

He passed both through his scanner. There was a chatter in his headphones. His eyes widened, he saluted smartly and stepped back. Having support at the highest level was some use after all.

That scene was repeated half a dozen times before I got out of Sydney onto the north coast tollway. There wasn’t much traffic. I supposed those who were going to flee Sydney had already done so, and I hardly saw a vehicle coming in. I drove all night, stopping for fuel and a greasy breakfast at dawn, then continuing.

Finally I turned off the tollway onto a winding road that led toward the mountains. It began to rain. We weaved up an escarpment and off onto a back road that was a series of potholes separated by greasy black mud. A few minutes later I went right, over a cattle grid, up a long overgrown drive and pulled up at a cottage set in a wild garden. I felt an overpowering sense of relief at coming home.

‘Whose place is this?’ asked Kirrily.

‘It’s ours. My mother owned it. This is where I lived when I was a kid.’ The place stirred childhood memories, mostly of playing by myself while my mother brooded.

‘Where are all the animals?’ She looked disappointed. I suppose she expected wallabies and wombats under every tree.

The cottage had not been rented for a few years. I didn’t have a key, couldn’t even remember which estate agent was in charge of the place. The doors were locked but one bathroom window was so rotten that I could lift the glass from its pane. We got in that way, unlocked the doors and opened the windows. There were mouse droppings everywhere, though the house wasn’t quite as dingy as the fourteen year old remembered it.

The electricity was turned off. By the time we’d made the place livable it was dark. I lit a fire and we sat in front of it, toasting bread on long forks and roasting apples next to the coals. It felt like an adventure together.

‘Tomorrow I’m going to go looking for frogs,’ said Kirrily. ‘I suppose you’ll be too busy to help. You always are.’

She didn’t sound angry, just resigned.

‘I’ll see,’ I said in that parently way. ‘I expect there’ll be plenty of frogs, in this weather.’

She sat looking out the window in the darkness, smiling dreamily. I felt more together with her than I had ever been. She ate her bread and began to hiccup.

I gave her my mother’s remedy, a teaspoon of sugar, but this time it did not work. The hiccups just went on and on. We thought it funny, at first. Then she threw up, right in front of the fire.

I cleaned it up, and her. As I was washing her face I noticed that her forehead was hot, and her eyes shiny. ‘Are you all right?’ I cried.

‘My head aches!’ she said in a croaky voice. ‘My stomach hurts too. I think I’ll go to bed.’

I made one up for her on the floor beside the fire. I gave her a big glass of water. In a panic, I fumbled out the PocketBook.

No signal, it said, even when I extended the aerial to the fullest. I felt like throwing it through the window. Then I remembered that we’d had satellite NetNews when I was a kid. I ran outside with the torch. The wind hurled rain at me. The dish was still there. I traced the wires down and found the outlet in the front room. I connected the wires to the universal access connector on the PocketBook. I didn’t expect it to work.

It didn’t. There must be a faulty connection somewhere. I scratched through the leather carry bag of the PocketBook for the manual. I looked up Satellite Access.

For normal satellite access, connect to the UA connector. To access the Tantalum satellite phone system, snap the receiving rod into the connector and rotate the arm until it points vertically. Certain kinds of roofing materials may interfere with reception. If no signal, try outside.

What receiving rod? I felt around in the bottom of the bag. Inside a pouch I found what looked like a metal rod with a cylindrical sleeve on one end and a snap connector on the other. I blessed Ben yet again, for having the best of everything. The Tantalum system was a commercial network mainly used by big business. I’d never used it, but I knew it was very reliable, provided access anywhere on earth, but was hideously expensive.

I installed the rod in the connector, rotated it into position, tapped in my bank account number and instantly the PocketBook beeped.

‘Ebola flu diagnosis!’ I snapped. I said it three times but the machine didn’t recognise the word. I gave up and typed it in. A list of symptoms appeared. They included fever, headache, vomiting, stomach pain and hiccups.

Not enough to be sure, but I didn’t feel in any doubt. In Kirrily’s age group the chance of dying was now 87%.

‘Treatment!’ I shouted at the machine.

NO VACCINE OR DRUG THERAPY AVAILABLE. PATIENT CARE: INTRAVENOUS DRIP TO MITIGATE SEVERE DEHYDRATION. BODY FLUIDS AND WASTES HIGHLY INFECTIOUS. ISOLATE PATIENT. USE PLASTIC SHEET OVER BED, WEAR FULL PROTECTIVE CLOTHING INCLUDING DOUBLE GLOVES. STERILISE BY AUTOCLAVING, WASHDOWN WITH DISINFECTANT. ALTERNATIVELY, 1:10 HOUSEHOLD BLEACH KILLS VIRUS INSTANTLY.

I wasn’t bothered about that. If she died, I would too. ‘Nearest hospital?’

I had to type that in as well. The computer industry had been boasting about speech recognition software for forty years, and it still didn’t work.

The nearest hospital was down on the coast, an hour and a half away. I carried Kirrily out to the car, wrapped in plastic bags against the rain. I could feel the heat radiating out of her.

We hadn’t gone more than a kilometre when I found the road blocked by a fallen tree. I stood in the rain, trying to think. It must have been pouring for days up here, for the ground was saturated. If I went off the road I’d be irretrievably bogged. I reversed back to the house, carried her inside and made a Triple 0 call on the PocketBook.

It took at least ten minutes for an answer.

ESTIMATED RESPONSE TIME, 36 HOURS.

I supposed half the population of Australia had an emergency at the moment.

I sat with her all night. The fever got worse. It had come on very suddenly. The old Ebola fever had usually taken days to develop. In the morning she was delirious, one minute shaking with chills, the next minute burning up. I opened her mouth to give her a drink and saw threads of blood oozing from her gums. The water went down but came up straight away, a thick red colour. I tried again. She brought it back up, every time.

I picked her up and immediately put her down again. Never had I felt so helpless. Where I had held her, purple bruises began to grow under her skin.

I sat by her side all day and the following night, watching her die and knowing there was nothing I could do about it. It made me question what my life had been for. Why had I spent the last eight years in pursuit of my mother’s dream? She had abandoned me!

This was my long overdue punishment. Surely I deserved to lose Kirrily, as I had lost my own daughter, and Jeffee, and Ben, and my mother. I deserved to be tormented for my monstrous crime.

Kirrily had not spoken for a day and a half. She didn’t recognise me now. Slowly but inevitably she was slipping into a coma from which she would never wake. I felt furiously angry with the world. How had this come about?

I called Triple 0 again.

ESTIMATED RESPONSE TIME, 36 HOURS.

I emailed the Centre, advising them of the situation and saying that I would not be in for a while. I did not tell them where I was.

6: Natural Solution

I couldn’t just sit here. I did a search on Ebola virus and went through all the work done by the World Health Organisation, the Institut Pasteur in Paris and the US Army Institute of Infectious Diseases, among others. I found nothing useful — it was all too old. I widened the search to include other filoviruses. That brought in a host of information, more than I could read in a year.

There had to be something! The virus couldn’t have come from nowhere. I had another idea. I used my high level access code to get into the Health Department’s data banks. They must know, by now, where the first contact had come from. My degree in Database Mining started to come in handy. I found thousands of documents — memos, answers to Question Time in Parliament, statistics on disease progress and variations, different symptoms, gene testing, mortality rates. But I couldn’t find the origin of the pandemic.

I tried the records of the Department of Immigration. My code let me in there, too. Working back from the date of the first casualty, and allowing for an incubation time of up to 21 days, I knew which dates to check.

There was little overseas travel in these days of recession and isolationism. Less than a hundred Australian residents and visitors had been in Central Africa in the time I was concerned with, and all had been examined. None showed any symptoms of the disease, or even any antibodies to it. That meant none had been in contact with the virus. A memo to the Health Department noted that Immigration had been unable to find any link to the African source area. There were no reported cases overseas, anywhere in the world. The pandemic was entirely confined to Australia.

What about Defence travel? I scanned through an organisation chart of the Defence Department while I wondered how to get into their systems. Suddenly I struck a familiar name — General Samuel Anders-Lofts, Deputy Chief of Staff. I recalled Ben saying that his uncle was a general. I noted his address, but my code would not let me into Defence’s network.

So how had the epidemic come about? What if the infection was deliberate, a new kind of terrorism? I searched for the records of the first victim, the man who had died so publicly on the NetNews. His name was Jasper Xavier Maxime. Unfortunately, every file came up with the same message.

ACCESS DENIED.

I tapped in my high level access code again.

ACCESS DENIED.

There was more than one way to dress a flea. I looked in the Directory. He was the only person in Australia with that name. He lived in the western suburbs of Sydney, out past Strathfield. I did a search in every database my codes allowed me access to: employment records, electoral rolls, criminal records, traffic offences, credit details. I did not find much.

Jasper Maxime had been single, mid-thirties, with no genetic deficiencies of even the most minor kind. Occupation — laboratory technician. He rented a one bedroom apartment, had been in the same job for ten years, had no criminal record. The most that could be said against him was a minor speeding fine and two parking tickets.

I realised that it was 3 a.m. I was exhausted and getting nowhere. I made some toast, heated a tin of soup in the fire and ate half of it. It was beef broth, quite flavourless. I diluted half a cup with warm water and fed it to Kirrily with an eye dropper. It stayed down, which seemed like a miracle. I sponged her forehead, wiped her mouth, lay down beside her and slept fitfully.

I jerked awake some hours later. It was morning, still raining. I’d found another way to attack the problem. The virus!

The results of genetic testing showed that it had an unusual structure. It was clearly derived from Ebola virus, but parts were so different that it was hard to see how they could have originated naturally.

This wasn’t a normal infection at all! I didn’t think it was terrorism, since no organisation had claimed responsibility. It had to be a laboratory escape. Someone in Australia must have been doing genetic manipulation of the virus. Illegal research — no Ethics Committee would ever have allowed such dangerous work!

And the first victim had been a laboratory technician. Which laboratory? I did a personnel search on all the laboratories in Australia that worked with human or animal viruses. There were only a few dozen and the name came up at once — the Centre for Advanced Bio-Engineering. The man worked at my own institute, where my sacred mother had carried out her research. And I, who had been put in charge of the investigation, had not been told. Clearly I was part of a cover up!

The research was a very well-kept secret, for I’d not had an inkling of it in the years I’d been at the Centre. But it was a very big institute, with more than a thousand staff and half a dozen laboratories across Sydney.

I wondered who the victim’s head of department had been. I searched that out, too. Prof. Eolie Chalmys. The Director of the Centre. My boss.

Where did the money come from? That wasn’t hard to find out. There were many documented sources of funding to the Centre, including a moderate-sized grant from the Medical Inspector’s Office which had been received every year for the past fifteen. But those grants were accounted for on programs I knew about. How was the Ebola research funded?

I used my mole program to crack into classified files I had no right to see. It was a huge risk. If they detected the entry they might trace me, and my career would be finished.

I continued anyway, and found evidence of three grants, identical large sums of money, provided by organisations I had never heard of. Shelf companies, set up specifically to hide the source of the funds.

That was as far as I got. I couldn’t find where the money originated, what research was being done on the virus, or what it was for. It was as if no records had ever been kept.

That was impossible. Most researchers spent more time writing grant applications and progress reports, and publishing scientific papers, than they did carrying out their research. It was worse than strange — it was highly suspicious.

The PocketBook began to beep urgently. One of Ben’s security programs had been activated.

WARNING! ENTRY DETECTED. LINKS BEING TRACED.

‘Who?’ I yelled at the mike.

HIGH LEVEL! CANCEL SEARCH?

I panicked and did an emergency shutdown. High level meant something higher than the police or even the Medical Board. Something like National Security. I must be close to uncovering something very nasty. Either incompetence on a grand scale, or worse!

More than a hundred thousand people were dead already. The truth about the epidemic would destroy hundreds of careers. My life, and Kirrily’s, weren’t worth a cent.

On the other hand, the good thing about using the Tantalum satellite uplink was that my account, and the records that could trace me to here, were on computer databases in the US. National Security must approach its US counterpart for the data. Procedures would have to be followed before the satellite company would part with the data. It gave me a little time, but I knew they’d find me within hours.

That thought was demolished by the next. Once Security identified me they’d know where to look. I’d been scanned at a dozen checkpoints since leaving home. This house was in my name.

Where could I go? With all the rain, I couldn’t drive anywhere that wasn’t a proper road. The only place I could go was into the forest. There was plenty of it around here. A skilled bushwalker could hide for months. But I wasn’t a skilled bushwalker and I had Kirrily. I couldn’t leave her. I’d been down that path before.

There was an old track, I remembered, that led across the paddocks a kilometer or so to the escarpment. The rugged slopes below that were clothed in rainforest. There were caves, too. We would have a last day together, if I could get Kirrily there.