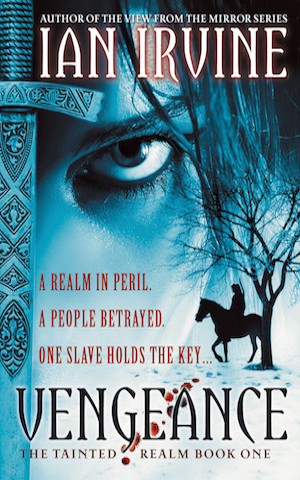

Book 1: The Tainted Realm

CHAPTER 1

‘Matriarch Ady, can I check the Solaces for you?’ said Wil, staring at the locked basalt door behind her. ‘Can I, please?’

Ady frowned at the quivering, cross-eyed youth, then laid her scribing tool beside the partly engraved sheet of spelter and flexed her aching fingers. ‘The Solaces are for the matriarchs’ eyes only. Go and polish the clangours.’

Wil, who was neither handsome, dextrous nor clever, knew that Ady only kept him around because he worked hard. And because once, years ago, he had revealed a gift for shillilar, the second sight. Having been robbed of their past, the matriarchs used even their weakest tools to protect Cython’s future.

Though Wil was so lowly that he might never earn a tattoo, he desperately wanted to be special, to matter. But he had another reason for wanting to look at the Solaces, one he dared not mention to anyone. He knew there was something wrong, something the matriarchs weren’t telling them. Perhaps – heretical thought – something they didn’t know.

‘You can see your face in the clangours,’ he said. ‘I’ve also fed the fireflies and cleaned out the effluxor sump. Please can I check the Solaces?’

Ady studied her swollen knuckles, but did not reply.

‘Why are the secret books called Solaces, anyway?’ said Wil.

‘Because they comfort us in our bitter exile.’

‘I heard they order the matriarchs about like naughty children.’

Ady slapped him, though not as hard as he deserved. ‘How dare you question the Solaces, idiot youth?’

Being used to blows, Wil merely rubbed his pockmarked cheek. ‘If you’d just let me peek …’

‘We only check for new pages once a month.’

‘But it’s been a month, look, look.’ A shiny globule of quicksilver, just fallen from the condenser of the wall clock, was rolling down its inclined planes towards today’s brazen bucket. ‘Today’s the ninth. You always check the Solaces on the ninth.’

‘I dare say I’ll get around to it.’

‘How can you bear to wait?’ he said, jumping up and down.

‘At my age, the only thing that excites me is soaking my aching feet. Besides, it’s three years since the last new page appeared.’

‘The next page could come today. It might be there already.’ Wil could not keep still. Though his eyes made reading a struggle, he loved books and everything about the Solaces; he ached for them so badly that his whole body trembled.

‘I don’t think any more pages are coming, lad.’ Ady pressed her fingertips against the blue triangle tattooed on her brow. ‘I doubt the fourteenth book will ever be finished.’

‘Then it can’t hurt if I look, can it?’ he cried, sensing victory.

‘I – I suppose not.’

Ady rose painfully, selected three chymical phials from a hexagonal rack and shook them. In the first, a watery fluid took on a subtle jade glow. The second thickened and bubbled like black porridge while the third crystallised to a network of needles that radiated pinpricks of sulphur-yellow light.

A spiral on the basalt door was dotted with phial-sized holes. Ady inserted the light keys into the day’s pattern and waited for it to recognise the colours. The lock sighed; the door opened into the Chamber of the Solaces.

‘Touch nothing,’ she said to the gaping youth, and bent over her engraving.

Unlike every other part of Cython, the chamber was uncarved, unpainted stone. It was a small, cubic room, unfurnished save for a white marble table with a closed book on its far end and, on the wall to Wil’s right, a four-shelf bookcase etched into solid rock. The third and fourth shelves were empty.

His eyes stung as he gazed upon the mysterious books he had only ever glimpsed through the doorway. After much practice he could now read a page or two of a storybook before the pain in his eyes became blinding, but only the secret books could take him where he wanted to go – to a world and a life not walled-in in every direction.

The top shelf contained five ancient Solaces, all with worn brown covers, and each bore the main title, The Songs of Survival. These books, vital though they had once been, were of least interest to Wil, since the last had been completed one thousand, three hundred and seventy-seven years ago. It was the future that called to him, not the dreary past.

On the second shelf were the volumes entitled The Lore of Prosperity. There were nine of these and the last five formed a set called Industry. On Delven had covers of white mica with topazes embedded down the spine, On Metallix was written in white-hot letters on sheets of beaten silver. Wil could not tell what On Smything, On Spagyric or On Catalyz were made from; his eyes were aching now, his sight blurring.

Nine books. Why were there nine books on the second shelf? The ninth, unfinished book, On Catalyz, should lie on the table, open at the last new page.

His heart bruised itself on his breastbone as he counted them again. Five books, plus nine. Could On Catalyz be finished? If it was, this was amazing news, and he would be the one to tell it. Yes, the last book on the shelf definitely said, On Catalyz.

Then what was the book on the table?

A new book?

The first new book in nine hundred and twelve years?

Magery was anathema to his people and Wil had never asked how the pages came to write themselves, nor how each new book could appear in a locked room in Cython, deep underground. Since magery was forbidden to all save their long lost kings, the self-writing pages were proof of instruction from a higher power. The Solaces were Cython’s sole comfort in their agonising exile, the only evidence that they still mattered.

We are not alone.

And only the Solaces could answer Wil’s painstakingly formulated question, for he no longer believed the story of his own people …

The cover of the new book was the dark, scaly grey of freshly cast iron. It was a small, thin volume, no more than thirty sheet-iron pages. He could not read the deeply etched title from this angle, though it was too long to be The Lore of Prosperity.

Wil almost choked and had to bend double, panting. Not just a new book, but the first of the third shelf, and no one else in Cython had seen it.

He turned to call Ady, then hesitated. She would shoo him away and the three matriarchs would closet themselves with the book for days. Afterwards they would conclave with the masters of the four levels of Cython, the Chief Chymizist, the heads of the other guilds, and the overseer of the Pale slaves. Then the new book would be locked away and Wil would go back to scraping muck out of the effluxors for the rest of his life.

This was his one chance to realise his dream. Just one page, that was all he asked. He glanced through the doorway. Ady’s old head was bent over her engraving but she would soon remember and order him back to work.

Now shaking all over, Wil took a step towards the marble table, and the ache in his eyes came howling back. He closed his worst eye, the left, and when the throbbing eased he took another step. For the only time in his life, he did feel special. He slid a foot forwards, then another. Each movement sent a spear through his temples but he would have endured a lifetime of pain for one page of the Solaces.

Finally he was standing over the book. From straight on, the etched writing was thickly crimson and seemed to ebb in and out of focus. He sounded out the letters of the title.

The Consolation of Vengeance.

‘Vengeance?’ Wil breathed.

Even a nobody like himself could tell that this book was going to turn their world upside-down. The other Solaces set out instructions for living underground: growing crops and farming fish, healing, teaching, mining, smithing, chymie, arts and crafts, order and disorder, defence. They described an existence that allowed no dissent and had scarcely changed in centuries.

But their enemy did not live underground – they occupied the Cythonians’ ancestral land of Cythe, which they called Hightspall. To exact vengeance, Cython’s armies would have to venture up to the surface, and even an awkward, cross-eyed youth could dream of marching with them.

Wil knew not to touch the Solaces; he had been warned a hundred times, but, oh, it was a new book and the temptation to be first was irresistible. He bent over it, pressing his lips to the cover. It was only blood warm, yet his tears fizzed and steamed as they fell on the rough metal. He wanted to bawl; wanted to slip the book inside his shirt, hug it to his bare skin and never let it go.

He shook off the fantasy; he was lowly Wil the Sump and he only had a minute. His trembling hand took hold of the cover. It was heavy as iron, and as he heaved it open it shed scabrous flakes onto the white marble.

The writing on the metal pages was the same sluggishly oozing crimson as on the cover, but his straining eye could not bring it into focus. Was it protected, like the other Solaces, against unauthorised use? On Metallix had to be heated to the right temperature before it could be read, while each completed chapter of On Catalyz required the light of a different chymical flame.

A mud-brain like himself would never decipher the protection. Frustrated, Wil flapped the front cover and a jagged edge tore his forefinger.

‘Ow!’ He shook his hand.

Half a dozen spots of blood spattered across the first page, where they set like flakes of rust. Then, as he stared, the script snapped into focus. Wil read the words and his eyes did not hurt at all. He turned the page, flicked blood onto the book again and read on.

‘I can see.’ His voice soared to freedom. ‘I can see.’

Ady shouted, ‘Wil, get out of there.’

He heard her scrambling across to the basalt door. The crimson letters brightened until they seared his eyes but Wil kept reading. ‘Ady, it’s a new book.’

‘What does it say?’ she panted from the doorway.

‘We’re leaving Cython.’ The rest of the book was blank, yet that did not matter – in his inner eye the future was unrolling all by itself. ‘I’m seeing a map,’ Wil whispered. ‘A map of tomorrow.’

For the remainder of her days the matriarch would regret not dragging him from the room but, at those words, tears of longing formed in her eyes and she gave way to her own desperate temptation. ‘Are you in shillilar? Where are the Solaces taking us? Are we finally going home?’

‘We’re going –’ In an instant, as though he had tumbled into a dyeing vat, the whole world turned crimson. ‘No!’ Will gasped, horror overwhelming him. ‘Stop her.’

Ady stumbled across and took him by the arm. ‘What are you seeing? Is it about me?’

Wil let out a cracked laugh. ‘I see her tearing up the map – changing the written future – bringing the plan to the brink –’

‘Who are you seeing?’ cried Ady.

‘A Pale slave, but –’

‘A slave?’

Wil tore his gaze away from the book for a second and gasped, ‘She’s still a child.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘I don’t know.’

A wild-eyed, frantic Ady shook him, crying, ‘When does this happen? How long have we got to find her?’

Wil turned back to the book. ‘Until … until she comes of age –’

The letters brightened until his eyes boiled out of his head, taking both sight and wits with it. Only the shillilar remained. Wil had longed to be special, and now he was, but there would be no solace in it. The dream had become his perpetual nightmare, one he had no means of articulating to the desperate matriarchs.

There was no way for them to contact the writer of the Solaces and warn him; they had to follow the plan. They could not think of disobeying the instructions inscribed in The Consolation of Vengeance, though they now feared that disaster would come of it.

But first the matriarchs had to do a terrifying thing – take action of their own accord, without advice. They had to secretly identify the slave child, one among eighty-five thousand Pale.

And see her dead.

***

CHAPTER 2

Whenever Mama wasn’t watching, the man that Tali called ‘Tinyhead’ poked his slimy white tongue out at her. There were black spots on it, like crawling blowflies. Tali had to turn away before she sicked up her breakfast.

Tinyhead was helping them to escape. In a thousand years, no Pale slave had ever escaped from Cython, and Mama had tears in her eyes whenever she talked about going home. Not wanting to upset her again, Tali clutched Mama’s hand more tightly and kept her worries to herself.

The further Tinyhead led them, the fiercer the tunnel art became. For an hour the walls were carved into the skeletons of burnt trees surrounded by ash like black snow. Then they walked along a dried-up river with water buffalo trapped in grey mud. Finally, as the passage became an endless desert where spiny lizards picked salt crystals off sharp rocks, Tinyhead heaved a stone door open and stood to one side so they could go through.

They had crossed into another world, one that was cold and dank and slimy underfoot. They were in a gloomy, unpainted cellar where green mist hung in the stagnant air. It looked like the inside of a mouldy old skull and the stink of poisoned rats made Tali gag.

‘Here you are.’ Tinyhead flopped his maggoty tongue out at Tali. ‘All your troubles are over, Pale.’

Mama whirled, reaching out to him, but he slammed the door in her face. She let out a whimper.

‘You’re hurting my hand, Mama,’ cried Tali.

Her mama crouched in front of Tali, holding her so tightly that she could hardly breathe. Mama’s blue eyes were wet, and Tali hated to see her so sad.

‘We’re betrayed, little one. We’re never going home.’

‘Why not?’ said Tali, looking around in confusion. Why had Tinyhead shut them in? What hadn’t she told Mama her fears? Was this her own fault?

A familiar face carved into the stone high on the wall made her shiver. It was Lyf, the enemy’s last and wickedest king, who had died long ago. She had often seen the tattooed Cythonians kneeling before his image.

To her left, a series of dusty stone bins ran along the wall. On the right, hundreds of wooden crates were stacked nearly to the ceiling. In the centre, thirty yards away, stood a stained black bench.

Something rustled, far across the cellar, and her mama looked around frantically. ‘Over here,’ she said, hauling Tali to the stacks of crates. ‘Squeeze into the middle where you can’t be seen.’

Tali clung to her. ‘I don’t like this place, Mama.’

‘Me either.’ Her mother looked around, frowning. ‘And yet, I feel close to our ancestors here. In, hurry.’

Tali was a good girl, so she bit her lip and edged into one of the gaps between the rotting crates. The floor was so slimy that her bare feet kept slipping.

‘Don’t cry. I know how brave you are.’ Her mama kissed her brow. ‘Tali,’ she choked, ‘– Tali, if I don’t come back, Little Nan will give you your Papa’s letter when you come of age.’

‘Mama?’ Why would she say such a thing? Of course she would come back.

‘Shh!’ Mama took Tali’s hands in her own and drew a ragged breath. ‘Tali, our family has a terrible enemy –’

The dead rat smell grew stronger. ‘Who, Mama?’

‘I don’t know. He’s never seen, never heard, but he flutters in my nightmares like a foul wrythen –’

‘You’re scaring me, Mama!’

‘When you’re older, you’ve got to find your gift and master it. It’s the only way to beat him.’

Tali shivered. In Cython, magery was forbidden. Magery meant death. Children were beaten just for whispering the word.

At a hollow click from the far side of the cellar, Mama jumped.

‘But Mama,’ said Tali, lowering her voice, ‘if our masters catch any slave using … magery, they kill them.’

‘Even innocent little children,’ said Mama, hugging her desperately. ‘So you must be very careful.’

‘Tell me what to do.’

‘I can’t. My gift doesn’t work any more.’

Tali’s voice rose. ‘Then how am I supposed to find mine?’

Mama clapped a hand over Tali’s mouth. ‘I don’t know, child. Don’t talk to anyone about your gift. You can’t trust anyone.’

Tali pulled away. ‘Is Tinyhead the enemy?’ She took hold of a splintered length of wood, wanting to jam it through his disgusting tongue.

‘Shh!’ said her mother. ‘You know what happens when you get angry.’

‘I’m already angry, and I’m going –’

‘Forget him. He’s nothing.’

‘When I find my gift, his head will be nothing. I’ll blast it right off.’

‘Tali, never say such things! You must lower your eyes and say, “Yes, Master.”’

‘I won’t!’ Tali said furiously. ‘I hate our masters and one day I’m going to escape.’

‘Yes, one day,’ said her mother dully. ‘But for now, promise you’ll be a good slave.’

‘I can’t.’

Her mama stroked Tali’s golden hair. ‘You may think whatever fierce thoughts you like, little one, for one day you will be the noble Lady Tali vi Torgrist, but in Cython you must always act the obedient slave.’

It frightened Tali to hear her mama say such things. ‘All right,’ she muttered. Tali had a bad temper, and knew it, but for Mama’s sake she would try. ‘I promise.’

Something made an ugly scraping sound, closer this time. Tali’s scalp felt as though grubs were creeping across it.

‘Keep still,’ Mama said softly. ‘Don’t look.’

‘Mama, what was that noise?’

‘I don’t know.’ Mama’s teeth chattered. ‘But whatever happens, even if your gift comes, don’t use it here.’

She darted away, blonde hair flying. Her bare feet skidded on the flagstones as she passed an ugly mural of three jackals fighting over the guts of a nobleman, recovered then zigzagged between piles of junk and the stone bins. Mama was a beautiful little bird, leading a cat away from her nest.

But as she passed between a pair of stone raptors with flesh-tearing beaks, two masked figures came after her. Tali clutched at a crate, her fingers sinking into powdery wood.

‘Mama, look out!’ she whispered, for the masks had fanged teeth and awful, angry eyes. ‘Don’t let them catch you.’

Then Mama slipped and twisted her ankle, and the moment they caught her Tali knew they were going to do something terrible.

‘No!’ she whimpered. ‘Mama, get away!’

The big man caught Mama’s arms and held her while his accomplice, a bony woman, punched her in the mouth.

‘Treacherous Pale scum,’ she snarled.

Mama sagged, staring at them like a mouse trapped by two cats, and Tali’s front teeth began to throb. Stop it, stop it! Mama, why don’t you fight back?

They dragged her to the black bench and the man heaved her onto it. The woman forced a green lump into Mama’s mouth, then passed a stubby rod back and forth over her head until the end glowed blue, scattering brilliant rays across the cellar. Mama moaned and her toes curled.

As the blue rod glowed more brightly, pain stabbed around the whorled scar on Tali’s left shoulder, her slave mark, and cold spread through her like venom. She shuddered and remembered to cover her eyes.

Born to slavery in underground Cython, she had learned life’s lesson in her stone cradle – obey, or suffer. But the people who held her mama weren’t tattooed like Cythonians, and they were too big to be Pale slaves. Who were they?

There came an ugly, splintery gouging sound and Mama shrieked.

‘Careful,’ the man cried. ‘He won’t pay if –’

‘It’s stuck,’ said the woman, and the gouging grew louder.

‘It’s got to be taken while she’s alive.’

‘Do you think I don’t know that?’ she hissed.

Tali peeped between her fingers and nearly screamed. Mama’s arms and legs were thrashing; green foam oozed from her nose and her hair dripped blood. Mama! Tali could not breathe; for a moment she could hardly see.

‘I can’t hold her.’ The man’s voice was hoarse, his eyes darting.

‘Nor me if you don’t!’ The woman’s arms were red to the elbows.

Why were they talking like that? Why were they hurting Mama? Tali’s breath came in painful gasps and her stomach was full of fishhooks. She had to help Mama. But Mama had told her not to move. Only magery could save Mama now, but she had told Tali not to use it here. Yet if she didn’t, Mama was going to die. But Tali had promised …

No! She had to break that promise, and if she got into trouble for it she would just take her punishment. Tali thought about the time she had used magery before, when she was little. She had been really angry about something and her gift had appeared out of nowhere. She tried to find those feelings again, to summon her magery, but Tali had been warned about her dangerous gift so many times, and was so afraid of it, that she could not find it anywhere.

It never came when she really needed it.

Then the carved face of Lyf appeared to shift, and yellow moved in its stone eyes. Again Tali’s slave mark burned and a sick despair overwhelmed her. She’d let Mama down again. Now a foggy hand reached out towards Mama, stretching and stretching as if to pluck something from her.

A flash, a zzzt that seemed like a spell going off and the air seemed to thicken like glue, blocking the hand, which faded out. The man and the woman froze, staring at the spot. Tali shivered. What was that?

The woman opened a pair of golden tongs behind Mama’s head, yanked, and Tali heard an awful, squelchy pop. Mama’s arms and legs jerked, then hung limp.

‘You’ve ended her,’ the man said hoarsely, shying away.

‘Who cares about a filthy Pale?’ said the woman. ‘I got it in time.’

Tali’s head spun and her eyes flooded; but for the crates she would have fallen down. Though she was only eight, she had seen all too many dead slaves. Why was this happening? Was it her fault? She should have run and led them away; she should have done something, anything. Had the evil woman killed Mama? No, she couldn’t be dead.

‘Mama, Mama!’ she whimpered, hurting all over.

The man gasped, ‘Did you hear a cry?’

You stupid fool, thought Tali. Now they’ll kill you too.

‘Are you impotent?’ said the woman. The man froze and she added, sneering, ‘Sorry, forgot your wee problem.’

The man drew a long knife and waved it at the woman. She laughed in his face. ‘Find the brat and finish it – if you’re capable.’

The man took a lantern in his free hand, and it was shaking. Though he was much bigger than the woman, he was afraid of her.

The woman removed something round from the tongs, like a black, bloody marble. ‘Oh!’ she whispered, ‘Oh, yes!’ and licked it clean. Through the holes in the mask, Tali saw her green eyes roll up until the whites were showing.

After checking that the man wasn’t looking, the woman filled a little, square bottle with Mama’s blood, twisted on a brass cap, licked bony fingers and thrust the bottle down her front.

Tali’s eyes burned and her nose was running. She wiped it on the back of her hand, fighting the urge to scream. If she made a sound, the man would cut her open like Mama. But she was much more scared of the evil woman with the crab-leg fingers and the frightening eyes. She pressed a finger to the slave mark on her left shoulder, for luck; touching it always made her feel better.

The man was tall and had a round, jiggling belly like a pudding basin. He was just outside her hiding place and she caught a glimpse of his gleaming knife blade, as long as her arm. Tali’s heart hammered; she recoiled and felt a shocking pain as a nail in one of the crates pierced her hip to the bone. Tears stung her eyes yet she dared not move. If she made a sound he would stab that knife right through her.

The man was breathing heavily and the spirits on his breath made her head spin. His hand shook as he raised the lantern, then lowered it. Silence fell, apart from a sickening drip-dripping from the black bench.

After Papa’s terrible death, Mama had taught Tali how to hide. ‘A slave must be invisible,’ she had said. ‘Never be noticed and you’ll be safe.’

No slave was ever safe, but Tali was the best at hiding among all the slave kids. She traced the loops and whorls of her slave mark with a fingertip, trying to find some comfort there, but nothing could comfort her now. Mama couldn’t be dead; it wasn’t possible, yet she was gone.

He waited, as if he knew she was there. What if he pulled the crates away? She had to do something. She felt among the broken wood on the floor for the sharpest length, a piece as long as her forearm. If he came at her, she would shove it into his fat belly and run.

Hr arm was trembling so much she could hardly hold the weapon. And then, to her shame, Tali realised that wee was running down her legs. She clamped her thighs together and, to distract herself, began to count her heartbeats, which were so loud that surely he could hear them. After another twenty beats, the man grunted and moved on. She kept still.

He sprang back, hacking at the crates with his knife and roaring, ‘Haaaaaa! Got you.’

Tali’s heart leapt up her throat and the nail ground into her hipbone, but she did not move. She was going to win this contest, for Mama.

Fifty heartbeats passed, then the man turned away. ‘Just rats,’ he said to the woman. ‘All done?’

‘No thanks to you.’

‘Come on. I need another drink.’

‘I’ll pour it down your throat until you choke.’

Tali eased off the nail, almost screaming with the pain. She pressed a fingertip against the wound, trying to heal it the way Nurse Bet had taught her, but the nail hole went too deep. The beads of blood on her fingers were as bright as jewels, as bright as Mama’s blood. Mama! Her eyes flooded again.

The woman pulled on a dangling rope and, with a screech, an iron staircase corkscrewed down. Tali felt sure the point at the bottom was going to twist right through Mama, but it brushed by her tiny waist before grounding on the black bench. The man shot up the steps, a rat running away from a ferret. The staircase was a coiled spring quivering under his weight.

But then – then the woman climbed onto the bench and stepped onto Mama’s chest as though she was a worthless piece of junk. One of Mama’s ribs snapped like the wishbone of a poulter and a scorching fury surged through Tali, an urge to smash the woman down. She fought it; Mama had told her to not make a sound.

The woman rocked back and forth as she scanned the cellar, crack-crack, standing on Tali’s beautiful mama as if she were a piece of firewood, then followed the man.

Once they were gone, Tali darted across and touched the crimson beads on her fingers to her mama’s bloody head, as if her own blood could heal Mama. Taking hold of her hand, she squeezed it tightly, trying to will Mama back to life, but the spirit had left her body forever.

She had told Tali not to fight back, to bow her head and say, ‘Yes, Master,’ and it had killed her. Tali wasn’t going to make that mistake.

Mama said it was wrong to hate people, but Tali’s rage had red-hot teeth and talons sharp as spikes. How dare they treat her beautiful mama that way?

‘When I’m grown up I’ll find you out,’ she whispered, hand upon her mother’s heart. ‘And once I get my gift I’ll hunt you down and make you pay.’

Then someone took a heavy breath, close by. The murderers! Coming back to kill her. Tali scuttled into the shadows between two of the stone bins. A grey stick protruded up from its broken top; she grabbed it and prepared to defend herself.

A handsome, black-haired boy, a few years older than herself, stumbled out from behind a heap of empty barrels. He wasn’t a slave, though, nor a tattooed Cythonian. He must have been rich, for he wore a plum-coloured velvet coat with solid gold buttons, an emerald kilt and shoes with shiny buckles. His face was white, his yellow vest was covered in vomit and his teeth were chattering.

But that wasn’t the only odd thing about him. The faintest misty aura, pale pink like the gills of a mushroom, clung to his head and hands. The aura of magery – though not his. Tali could tell that he had no more gift than a log.

The rich boy reached out towards Mama then drew back sharply, staring at his hands. Tali’s hair stood up. His hands were covered in blood, yet he hadn’t touched Mama.

He doubled over, sicked onto his shoes and let out the awful moan of an animal in pain. Tali must have made a sound for his head shot around and he stared at her, then bolted up the stair, yanking on the rope as he went. The iron stair howled as it rose with him out of sight.

Tali could hold back no longer. ‘I’m going to get you!’ she shouted, brandishing the stick. It felt good in her hand; it felt as though it was on her side. A trapdoor clanged shut and the green light began to fade.

What if Tinyhead was waiting outside and had heard her? Tali shivered. What if he came after her? Damn him! Mama had trusted Tinyhead and he had betrayed her. He had to pay. Rage swelled until her heart felt as if it was going to explode, then she pointed the stick at the stone door, willing Tinyhead’s head to burst like a melon. With a sudden gush, the pressure was gone and her rage as well.

The yellow eyes in the carved face were staring at her now, smoking with fury. She pointed the stick at them but nothing happened, then the eyes were empty again, the carving no more than grimy stone.

She was holding the stick so tightly that her knuckles hurt. For the first time Tali saw it clearly and it wasn’t a stick. It was a bone, a old human thigh bone, but there was nothing horrible about it; oddly, it felt like a friend.

Tali put it back where she had found it, and suddenly felt so exhausted that she could barely stand up, She stumbled to the door, trying not to think about the man with the knife or the woman and her golden tongs, trying to wipe out the memories forever. When she slipped into the painted tunnel that led back to Cython, there was no sign of Tinyhead.

Learn to lower your eyes and say, ‘Yes, Master’.

‘All right!’ Tali said savagely. ‘But once I come of age, once I find my gift, look out!’

How could she find her gift when she couldn’t trust anyone? How could she beat her enemy when no one knew who he was? Blinded by scalding tears, she crept home to Cython, and slavery.

At least she would be safe there.