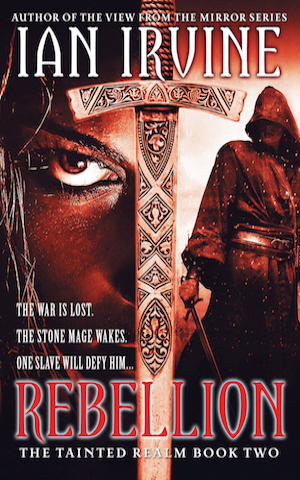

Book 2: The Tainted Realm

CHAPTER 1

‘Lord Rixium?’ The girl sounded desperate. ‘You gotta get up now. The enemy are coming. Coming fast.’

Rix’s right wrist throbbed abominably, and so did the back of his head. He groaned, rolled over and cracked his ear on a stone edge. His cheek and chest were numb, as if he’d been lying on ice.

‘What …?’ he mumbled. ‘Where –?’ His eyes were gummed shut and he didn’t want to open them. Didn’t want to see.

‘Chancellor’s stolen Tali and Rannilt away, to milk their healing blood.’

He recognised her voice now. A maidservant, Glynnie.

‘And Lord Tobry’s been chucked off the tower, head-first. Splat!’ said a boy’s voice from behind Rix.

‘Benn!’ Glynnie said sharply.

Rix winced. Did he have to be so matter-of-fact about it? ‘Tobe was my oldest friend.’

‘I’m sorry, Lord,’ said Glynnie.

‘How long was I out?’

‘Only five minutes, but you’re first on their death list, Lord. If we don’t go now, we’re gonna die.’

‘Don’t call me Lord, Glynnie.’

‘Lord?’

‘My parents were executed for high treason,’ he said softly. ‘House Ricinus has fallen, the palace lies in ruins and I betrayed my own mother. I am utterly dishonoured. Don’t – call – me – Lord!’

‘R-Rixium?’ She tugged at his arm, the good one.

‘That’s what my murdering mother called me. Call me Rix.’

Glynnie rubbed his eyelids with her fingertips. The sticky secretions parted to reveal a slender servant girl, seventeen years old. Tangled masses of flame-coloured hair, dark green eyes and a scatter of freckles on her nose. Rix had not yet turned twenty yet he felt a lifetime older. Foul and corrupt.

‘Get up,’ she said.

‘Give me a minute.’

They were on the top of his tower, at the rear of what remained of Palace Ricinus. From where Rix lay he could not see over the surrounding wall, and did not want to. Did not want to see the ruin a hundred-foot fall had done to his dearest friend.

A freezing wind carried the stink of burned deer meat, the forgotten skewers Glynnie had been cooking over the embers of Rix’s artist’s easel. He would never paint again. Beside the fire stood a wide-eyed boy of ten, her little brother. A metal drinking cup sat on the stone floor. Some distance away lay a bloody sword. And a small puddle of blood, already frozen over.

And a right hand, severed at the wrist.

Rix’s right hand.

Something collapsed with a thundering crash not far away, and the tower shook.

‘What was that?’ said Rix.

She ran to the wall, went up on tiptoes and looked over. ‘Enemy’s blasting down the palace towers.’

‘What about Caulderon?’

Her small head turned this way and that, surveying the great city. What was left of it.

‘There’s smoke and flame everywhere. Rix, they’re coming. Tell me what to do.’

‘Take your brother and run for your life. Don’t look back.’

‘We’ve nowhere to go, Lord.’

‘Go anywhere. It’s all the same now.’

‘Not for us. We served House Ricinus; we’re condemned with our house.’

‘As am I,’ said Rix.

‘We swore to serve you. We’re not running away.’

‘Lyf hates Herovians, especially me. He plans to put me to death. But he doesn’t know you exist.’

‘I’m not leaving you, Lord – Rix.’

Rix did not have the strength to argue. ‘What about Benn? If the Cythonians find him with me, they’ll kill him too.’

‘Not runnin’ either,’ said Benn. ‘We can’t break our sworn word, Lord.’

Unlike me, Rix thought bitterly. The servants outreach the master. ‘Ah, my head aches.’

‘That mongrel captain knocked you out,’ said Glynnie. ‘And the chancellor – he –’ Her small jaw tightened. ‘He’s a useless, evil old windbag. He’s lost Caulderon and he’s going to lose the war. No one can save us now.’

‘You can, Lord,’ said Benn, his eyes shining. ‘You can lead Hightspall to victory, I know it.’

‘Hush, Benn,’ said Glynnie. ‘Poor Rix has enough troubles as it is.’

But he could see the light in her eyes as well, her absolute belief in him. It was an impossible burden for a condemned man and he had to strike it down. Hightspall was lost; nothing could be done about it.

‘Benn,’ he said softly, speaking to them both. ‘I can’t lead anyone. The chancellor has destroyed my name and all Hightspall despises me –’

‘Not all, Rix,’ said Glynnie. ‘Not us. We know you can –’

‘No!’ he roared, trying to get up but crashing painfully onto his knees. ‘I don’t even believe in myself. No army would follow me.’

Benn’s face crumpled. ‘But, Lord –’

‘Shhh, Benn,’ said Glynnie hastily. ‘Let me help you up, Lord.’

She was stronger than she looked, but Rix was a huge man and it was a struggle for her to raise him to his feet. The moment he stood upright it felt as though his head was going to crack open. Through a haze of pain and dizziness he heard someone shouting orders.

‘Search the rear towers next.’ The man had a heavy Cythonian accent.

‘Where are we going, Rix?’ said Glynnie.

He swayed. She steadied him.

‘Don’t know.’ He looked around. ‘I need Maloch. It’s enchanted to protect me.’

That was ironic. A command spell cast on Rix when he was a boy of ten had left him with a deep-seated fear of magery, and recent events had proven his fear to be justified.

‘Didn’t do a very good job,’ she sniffed. ‘Benn, get Rix’s sword. And … and bring his hand.’

‘His hand?’ Benn said in a squeaky voice. ‘But – it’s all bloody … and dead …’

‘I’m not leaving it for the crows to peck. Fetch the cup, too.’

Benn handed the ancient, wire-handled sword to Rix, who sheathed it left-handed. The roof door stood open. Glynnie helped him through it and onto the steep stair that wound down his tower. Rix swayed, threw out his right arm to steady himself and his bloody stump cracked against the wall.

‘Aaarrgh!’

‘Sorry, Lord,’ whispered Glynnie. ‘I’ll be more careful.’

‘Stop apologising. It’s not your damn fault.’ Rix pulled away from her. ‘I’ve got to stand on my own feet. It’s only a hand. Plenty of people have survived worse.’

‘Yes, Lord.’

But few men had lost more than Rix. He’d been heir to the biggest fortune in the land, and now he had nothing. His family had been one of the noblest – for a few moments, House Ricinus had even been a member of the First Circle, the founding families of Hightspall. Then the chancellor, out of malice, had torn it all down.

Rix’s parents had been hung from the front gates of the palace, then ritually disembowelled for high treason and murder, and everything they owned had been confiscated. Now, not even the most debased beggar or street girl was lower than the sole surviving member of House Ricinus.

Rix had also been physically perfect – tall, handsome, immensely strong, yet dextrous and fleet – and accomplished. Not just a brilliant swordsman, but a masterful artist – the best of the new generation, the chancellor had said in happier times. Now Rix was maimed, tainted, useless. And soon to die, which was only right for a man so dishonourable that he had betrayed his own mother. As soon as Glynnie and Benn got away, he planned to take the only way out left to him – hurl himself at the enemy, sword in hand, and end it all.

He reached the bottom of the tower stair, ignored Glynnie’s silent offer of help and lurched into his ruined studio. When Tobry had smashed the great heatstone in Rix’s chambers the other day, and it burst asunder, it had brought down several of the palace walls. There were cracks in the walls and part of the ceiling had fallen. The scattered paints, brushes and canvases were coated in grey dust. He crunched across chunks of plaster, stolidly looking ahead. He yearned for the solace of his art but had to put it behind him. Forever.

‘Where we going, Lord?’ Glynnie repeated.

‘How the hell would I know?’

Not far away, sledge hammers thudded against stone and axes rang on timber. The Cythonians were breaking in and they would come straight here.

‘We’re trapped,’ said Glynnie, her jaw trembling. She stretched an arm around Benn and hugged him to her. ‘They’re going to kill us, Lord.’

‘You could go out the window –’

Rix looked down. From here the drop was nearly thirty feet. If they weren’t killed outright, they’d break their legs, and in a city at war that meant the same thing. He cursed inwardly, for it left him with no choice. Glynnie and Benn were his people, all he had left, and as their former lord he had a duty to protect them. A duty that outweighed his longing for oblivion. He would devote his strength to getting them out of Caulderon, and to safety. And then …

He headed down the steps into his once-magnificent, six-sided salon, now filled with rubble, dust and smashed, charred furniture. The crashing was louder here. The enemy would soon break through. The only hope of escape, and that a feeble one, was to go underground.

‘Get warm clothing for yourself and Benn,’ he said to Glynnie. ‘And your money. Hurry!’

‘Got no money,’ said Glynnie, trembling with every hammer and axe blow. ‘We got nothing, Lord.’

‘Tobry –’ Rix choked. How was he ever going to do without Tobry? ‘Tobry brought in spare clothes for Tali. She’s nearly your size. Take them.’

She stood there, trembling. ‘Where, Lord?’

‘In the closet in my bedchamber. Run.’

He still had coin, at least. Rix filled a canvas money belt with gold and other small, precious items and buckled it on one-handed. He packed spare clothing into an oilskin bag to keep it dry, and put it, plus various other useful items, into a pack.

The crashing grew louder, closer. Glynnie filled two another oilskin bags, packed two small packs and dressed herself and Benn in such warm clothes as would fit. She strapped on a knife the length of her forearm and collected the dusty food in the salon.

‘They’re nearly through,’ she said, white-faced. ‘Where are we going, Lord?’

Benn still held Rix’s severed hand in his own small, freckled hand. His wide grey eyes were fixed on Rix’s bloody stump. Benn caught Rix’s gaze, flushed and looked away.

Rix gestured to a broad crack, low down in the wall at the back of the salon. The edges resembled bubbly melted cheese, the plaster and stonework etched away and stained in mottled greens and yellows.

He hacked away the foamy muck to reveal fresh stone, though when he flicked the clinging stuff off the knife the blade was so corroded that it snapped. He tossed it into the rubble. Benn ran back and fetched him another knife.

‘Go through,’ said Rix. ‘Don’t touch the edges.’

‘What is that stuff?’ said Benn.

‘Alkoyl. Mad Wil squirted it around the crack to stop us following him.’

‘What’s alkoyl?’

‘An alchymical fluid, the most dangerous in the world. Dissolves anything. Even stone, even metal – even the flesh of a ten-year-old boy.’ Rix took Benn’s free hand and helped him though.

‘We’ll need a lantern,’ said Glynnie.

‘No, they’d track us by its smell,’ said Rix.

He handed the boy a glowstone disc, though its light was so feeble it barely illuminated his arm. Tobry, an accomplished magian, could have coaxed more light from it, but – Rix avoided the rest of the thought.

‘We’ll need more light than that,’ said Glynnie.

She bundled some pieces of wood together from a broken chair, tied them together with strips of fabric, tied on more fabric at one end and shoved it in her pack.

They went through, holding their breath. The crack snaked ever down, shortly intersecting a network of other cracks that appeared to have freshly opened, and might close again just as suddenly.

‘If they shut, they’ll squeeze the juice out of us like a turnip,’ whispered Glynnie.

Rix stopped, frowning. ‘Can you smell alkoyl?’

‘No,’ she said softly, ‘but I can smell stink-damp.’

‘That’s bad.’

Stink-damp smelled like rotten eggs. The deadly vapour seeped up from deep underground and collected in caverns, from where it was piped to the street lamps of Caulderon and the great houses, such as Palace Ricinus. Stink-damp was heavier than air, however. It settled in sumps, basements and other low places, and sometimes exploded.

‘I can smell alkoyl,’ said Benn.

‘Good man,’ said Rix. ‘Can you follow it?’

‘I think so.’

Benn sniffed the air and moved down the crack.

‘Why are we following alkoyl?’ said Glynnie.

‘Wil was carrying a tube of it,’ said Rix. ‘He also stole Lyf’s iron book, and if anyone can find a safe way out of here, Wil the Sump can, the little weasel.’

‘Isn’t he dangerous?’

‘Not as dangerous as I am.’

The boast was hollow. Down here, Rix’s size put him at a disadvantage, whereas Wil could hide in any crevice and reach out to a naked throat with those powerful strangler’s hands.

They squeezed down cracks so narrow that Rix could not take a full breath, under a tilted slab of stone that quivered at the touch, then through an oval stonework pipe coated with feathery mould. Dust tickled the back of Rix’s throat; he suppressed a sneeze.

After half an hour, Benn could no longer smell alkoyl.

‘Have we gone the wrong way?’ said Rix. ‘Or is Wil in hiding, waiting to strike?’

Neither Glynnie nor Benn answered. They were at the intersection of two low passages that burrowed like rat holes through native rock. Many tunnels were known to run under the palace and the ancient city of Caulderon, some dating back thousands of years to when it had been the enemy’s royal city, Lucidand; others had been forgotten long ago. Rix’s wrist, which had struck many obstacles in the dark, was oozing blood and throbbing mercilessly.

‘Lord?’ said Glynnie.

He did not have the energy to correct her. ‘Yes?’

‘I don’t think anyone’s following. Let me bandage your wrist.’

‘It hardly matters,’ he said carelessly. ‘Someone is bound to kill me before an infection could.’

‘Sit down!’ she snapped. ‘Hold out your arm.’

An angry retort sprang to his lips, but he did not utter it. He had been about to scathe Glynnie the way his late mother, Lady Ricinus, had crushed any servant with the temerity to speak back to her. Yet Rix was forsworn and a condemned man, while Glynnie had never done other than to serve as best she could. She was the worthy one; he should be serving her.

‘Not here. They can come at us four ways. We need a hiding place with an escape route.’

It took another half hour of creeping and crawling before they found somewhere safe, a vault excavated from the bedrock. It must have dated back to ancient times, judging by the stonework and the crumbling wall carvings. A second stone door stood half open on the other side, its hinges frozen with rust. To the left, water seeped from a crack into a basin carved into the wall, its overflow leaving orange streaks down the stone.

‘I don’t like this place,’ said Benn, huddling on a dusty stone bench, one of two.

‘Shh,’ said Glynnie.

In the far right corner a pile of ash was scattered with wood charcoal and pieces of burnt bone, as if someone had cooked meat there and tossed the bones on the fire afterwards.

Rix perched on the other bench and extended his wrist to Glynnie. ‘Do you know how to treat wounds?’

‘I can do everything.’ It was a statement, not a boast.

‘But you’re just – you’re a maidservant. How do you know healing?’

She pursed her lips. ‘I watch. I listen. I learn. Benn, bring the glowstone. Rix, hold this.’

Gingerly, as though she would have preferred not to touch it, she pressed Maloch’s hilt into Rix’s left hand.

‘Why?’ he said.

‘It’s supposed to protect you.’

‘Only against magery.’

She knelt in the dust before him, then took a bottle of priceless brandy from her pack, Rix’s last surviving bottle, and rinsed her hands with it. She laid a little bundle containing rags, needle and thread and scissors on her pack, poured a slug of brandy onto a piece of linen and began to clean his stump.

Rix tried not to groan. Blood began to drip from several places. By the time she finished, Glynnie was red to the elbows.

He leaned back against the wall and closed his eyes, for once content to do as he was told.

‘Hold his wrist steady, Benn,’ said Glynnie.

A pair of smaller, colder hands took hold of Rix’s lower arm. He heard Glynnie moving about but did not open his eyes. She began to tear linen into strips. Liquid gurgled and he caught a whiff of the brandy, then a chink as she set down a metal cup.

‘I could do with a drop of that,’ he murmured.

Glynnie gave a disapproving sniff. She was washing her hands again.

‘Steady now,’ she said. ‘Hold the sword. This could hurt.’

She began to spread something over his stump, an unguent that stung worse than the brandy. Rix’s fingers clenched around Maloch’s hilt.

‘Ready, Benn?’ said Glynnie.

‘Yes,’ he whispered.

Her hand steadied his wrist. There came a gentle, painful pressure on the stump. Where his fingers touched the hilt, they tingled like a nettle sting. Then Rix felt a burning pain as though she had poured brandy over his stump and set it alight. His eyes sprang open.

Glynnie had pressed his severed hand against the stump, and now the pain was running up his arm and down into his fingers. Blue were-flames flickered around the amputation then, with the most shocking pain Rix had ever experienced, the bones of his severed hand ground against his wrist bones – and seemed to fuse.

He had the good sense not to move, though he could not hold back the agony. It burst out in a bellow that sifted dust down from the roof onto them, like a million tiny drops falling through a sunbeam.

‘What are you doing to me?’

CHAPTER 2

Benn let go and scrambled backwards into the dark, out of harm’s way.

Glynnie went so pale that the freckles stood out down her nose. She swayed backwards as though afraid Rix was going to strike her, but her bloody hands were rock-steady, one on his wrist, the other on his partly re-joined hand.

‘Don’t move!’ she said.

Hope and fear went to war in Rix. The foolish, foolish hope that Glynnie knew what she was doing and could give him his right hand back. And the gut-crawling fear that it would go desperately wrong and would be worse than having a stump on the end of his arm. He clutched the hilt of Maloch so hard that it hurt – and prayed.

How could it work? She had no gift of magery. Neither was she a healer. She was just a maidservant who had picked up a few tricks in the healery.

It was impossible to keep still. The pain was a dog mauling his wrist, splintering the bones. Then, out of nowhere, he felt his amputated hand as an ice-cold, dangling extremity. He felt the blood oozing sluggishly through each of the collapsed veins, dilating them one by one.

His hand was no longer cold, no longer grey-blue. A warm pinkness was spreading through it. Red scabs formed in three places across his wrist and slowly extended along the amputation line until they ran most of the way around, though a spot near his wrist bone, and another underneath, still ebbed blood.

His little finger twitched; pins and needles pricked all over his hand. And then –Rix flexed his index finger, and it moved. Tears sprang to his eyes.

‘How did you do that?’ he said hoarsely. ‘Who are you?’

Glynnie shook her head, slumped onto the other bench and wiped her brow with her forearm, leaving a streak of blood there. ‘I’m not a healer, nor a magian – just a maidservant.’

‘I don’t understand …’

Glynnie tilted the metal cup towards him. The bottom was covered with a smear of blood.

‘What’s that for?’ said Rix.

‘It’s the cup Tali used to try and heal Tobry. With her healing blood.’

‘But she didn’t heal him. He’s dead.’

‘Maybe shifters can’t be healed,’ said Glynnie. ‘But Tali’s blood can heal ordinary wounds. That’s all I did.’

‘Go on.’

‘I covered both edges of your wrist with the blood left in the cup. It was frozen; I had to warm it in my hands. I pushed your hand and wrist together and held them. That’s all.’

Rix’s other hand was still clenched tightly around Maloch’s hilt. He let go. ‘You also used the protective magery of my sword.’

‘I didn’t use it,’ said Glynnie. ‘I only put it where it could do you some good.’

‘You gave me back my hand. I can never thank you –’

‘It could get infected,’ said Glynnie. ‘I’ll have to look after it.’

She stood up, swaying with exhaustion, and Rix realised how much he had taken her for granted. Why should the great Lord Rixium notice a little, freckled maidservant? Palace Ricinus had employed a hundred maids, each as replaceable as every other.

‘Sit down,’ he said, reaching up to her. ‘Rest. Let me wait on you.’

Her eyes widened; a blotchy flush spread across her cheeks. ‘You can’t wait on me.’

Glynnie washed the blood off her hands and forearms in the basin niche, then took a rag from her pack and scrubbed Benn’s grubby face and hands. He was half asleep and made no protest. She cleaned her blood-spotted garments as best she could, took stale bread and hard cheese from her pack, cut a portion for Rix and another for her brother, then a little for herself. She resumed her seat, nibbled at a crust, leaned back and closed her eyes. The flush slowly faded.

Her eyes sprang open. ‘Lord, we got to fly. They could be creeping after us right now.’

‘Maloch will warn me. Rest. You’ve been up all night.’

‘So have you.’

‘I couldn’t sleep even if I wanted to. Hush now. I need to think.’

It was a lie. So much was whirling through his mind that he was incapable of coherent thought. Rix clenched his right fist, for the pleasure of being able to do so. It did not feel as natural as his left hand, and the scabbed seam around his wrist would leave a raised scar, but he had his hand back, and it worked. He could ask for nothing more.

‘How did you know it would re-join, Glynnie?’

‘Didn’t. But the captain cut your hand off with that sword …’

‘Yes?’ he said when she did not go on.

‘It’s supposed to protect you. So I thought … I thought it might not have severed your hand on all the levels …’

‘What do you mean, all the levels?’

‘I don’t know. Heard it mentioned by the chancellor’s chief magian one time … when …’

‘When you were watching and listening?’ said Rix.

‘Servants spend half their time waiting,’ said Glynnie. ‘I like to make sense of things. I thought, if your hand hadn’t been severed on all the levels, it might join up.’

He rested his back against the wall. Though it was deep winter in Caulderon, this far below the palace it was pleasantly warm. He raised his hand. Two places were still ebbing blood, though they were smaller than before. The healing was almost complete.

He closed his eyes for a minute, but felt himself sinking into a dreamy haze and forced them open. The enemy were too many and too clever. It would not take them long to discover which way he had gone, and if he were asleep he might miss Maloch’s warning.

He rose, paced across the square vault and back. Then again and again. His eyes were accustomed to the dimness now and the glowstone shed light into the corners of the vault. It must have been built in olden times, for the stonework was unlike anything he had seen before. The wall stone was as smooth as plaster, yet the door frame, and each corner of the wall, was shaped from undressed stone, rudely shaped with pick and chisel. It was odd, yet seemed right.

These walls are crying out for a mural, he thought, and his hand rose involuntarily to the wall, as though he held a brush. He cursed, remembered that there was a child present and bit the oaths off. Again his hand rose. Painting had been his solace in many of the worst times of his childhood, and Rix longed for that solace now.

‘Lord?’ said Glynnie, softly.

‘It’s all right. I’ll wake you if anything happens. Sleep now.’

She trudged across, holding out a long object, like a stick or baton, though it took a while for him to recognise it as one of his paint brushes.

‘Thought you might need it,’ she said.

‘After I finished the picture of the murder cellar, I swore I’d never paint again.’

‘Painting is your life, Lord.’

‘That life is over.’

‘It might help to heal you.’

He took the brush. His restored hand felt like a miracle, but it would take a far greater one to heal the inner man who had betrayed his mother and helped to bring down his house.

Yet if he could lose himself in his art, even for a few minutes, it would do more for him than a night’s sleep. Rix set down the brush, since he had no paint, and looked for something he could use to sketch on the wall. There was charcoal in the ashes of the ancient campfire though, when he picked it up, the pieces crumbled in his hand.

Behind the ashes he spied several lengths of bone charcoal. He reached for a piece the length of his hand and the thickness of his middle finger. His fingers and thumb took a second to close around it, then locked. He began to sketch on the wall. His hand lacked its previous dexterity so he drew with sweeps of his arm.

He had no idea what he was drawing. This was often the case when he began a work – it worked better if he did not think about the subject. On one notable occasion he had done the first sketch blindfolded, and the resulting painting had been one of his best. The chancellor had called it a masterpiece.

It had also been a divination of the future, and Hightspall’s future was bleak enough already. If there was worse to come, he did not want to know about it in advance.

As he worked, Rix tried to work on an escape plan. It would not be easy, for the enemy occupied the city and guarded all exits. They knew what he looked like and, being one of the biggest men in Caulderon, he had no hope of disguising himself. There were many tunnels and passages, of course, and some led out of the city, but the enemy were masters of the subterranean world and he had little hope of escaping them there. No hope! The tunnels would be patrolled by were-jackals and other shifters. They could sniff him out from a hundred yards.

That only left the lake. Having dwelt underground for well over a thousand years, the Cythonians could have little knowledge of boats, while Rix had been sailing since he could walk. And many forgotten drains led to the lake. Some had been exposed by the great tidal wave several days ago, burst open by the pressure of water. If he could get Glynnie and Benn onto a boat, they would have a hope.

The worn length of bone charcoal snapped. He selected another from the ashes and sketched on.

If he succeeded in escaping, where could he go? Hightspall was almost ice-locked. For centuries the ice sheets had been spreading up from the southern pole to surround the land, as they had already enveloped the long, mountainous island called Suden. Southern Hightspall was mostly open farmland that offered few hiding places; his way must be to the rugged west or the even more mountainous north-east.

He had lost everything, but the chancellor had also given him something – the Herovian heritage Rix had not known he had. He ran his fingers along the weathered words down Maloch’s blade – Heroes must fight to preserve the race. Who were the Herovians, anyway? They had come here two thousand years ago on the First Fleet, a persecuted minority following a path set down in their sacred book, the Immortal Text, searching for their Promised Realm.

They had been led by Axil Grandys, the founder of Hightspall, and his allies who together made up the Five Herovians, or Five Heroes, as they were to become known.

‘It’s beautiful,’ sighed Glynnie. ‘Where is it?’

Rix focused on his sketch, almost afraid to look. It showed a pretty glade by a winding stream, the water so clear that cobbles in the stream bed could clearly be seen. Wildflowers dotted the grass. Hoary old trees framed the glade and in the distance was a vista of snowy mountains.

He let out his breath with a rush. ‘I don’t know. I’ve never seen the place before.’

Glynnie returned to the bench, put her arm around Benn and her eyes closed. For the first time since he had known her, she looked at peace. Rix laid down the charcoal, sat on a block of stone and compared his hands. His wrist still throbbed and his fingers tingled. When he opened and closed his hand it moved stiffly, though less stiffly than before, he fancied.

One of the ebbing wounds had closed; the other still oozed blood. Idly, Rix wiped it away with the paintbrush, then studied his blood in the bluish light of the glowstone. It looked richer than before, almost purple. He admired the colour for a moment, as artists are wont to do then, without thinking, stepped across to the sketch and began to paint.

When the brush was empty he touched up his sketch with the charcoal, using his left hand. Taking more blood on the paintbrush he continued, eyes unfocused so he could not influence the work, painting on blind inspiration.

After half an hour he began to feel weary and drained. He often did at the end of a painting session. He dabbed at his wrist but it was no longer bleeding. The last section of the wound had sealed over and he had nothing left to paint with.

He glanced at the stick of charcoal and saw that that it wasn’t some animal bone, tossed onto the fire after dinner. It was a part of a human arm bone, the smaller bone of the forearm.

Rix tossed it away with a shudder and let the brush fall. He slumped onto his seat, head hanging, arms dangling, longing to lie down and sleep. He fought it; the longer they delayed, the more difficult it would be to get out of Caulderon. He shivered. Why was it so cold? His fingers were freezing.

The fingers of his right hand were hooked and he could not straighten them. They no longer moved when he willed them to. And they were cold; dead cold. The tips of his fingers weren’t pink any more, but blue-grey, and grey was spreading towards his hand.

‘Lord, what have you done?’ cried Glynnie.

He started and looked around wildly. She was on her feet, staring at the painting on the wall. Red as blood it was, black as charred bone. Rix blinked at it, rubbed his eyes and recoiled.

It still showed the glade by the stream, but it was no longer enchanting. The sky was blood-dark and its reflection turned the water the same colour. There were two figures in the clearing now, a man with a sword and a woman with a knife. No, three. The third was up against the trunk of the largest tree, chained to it, helpless.

It was Tobry, and his shirt had been torn open, baring his chest.

The man was Rix, the woman, Tali, and they were advancing on Tobry, preparing to murder their best friend. But he was already dead, so what could it mean? Was it meant to symbolise the way Tali and Rix had, without meaning to, destroyed Tobry’s last hope, leaving him with no choice but to sacrifice himself to the fate he most feared? Could the mural be an expression of Rix’s own sickening guilt? Or did he bear a secret resentment because the chancellor had forced Rix to choose between Tobry’s life and betraying his own, evil mother?

Am I even more dishonourable than I’ve been made out to be? Rix thought.

Cold rushed along the fingers of his right hand, then across his hand to the wrist. Blue followed it, slowly turning grey. All feeling vanished down to the wrist and Rix felt sure it would never come back.

Henceforth he would go by another name.

Deadhand.

CHAPTER 3

Like the first trickle down a drought-baked river bed it came. But it wasn’t a river bed, it was a paved corridor whose stone walls were carved into scenes of nature – it was the main tunnel in the underground city, Cython. It wasn’t water either, for it was thick and red and sluggish, and had a smell like iron.

‘Bare your throat,’ said the chancellor’s principal healer, Madam Dibly, a scrawny old woman with a dowager’s hump.

Tali was jerked out of her daze and the vision of that red flood vanished. ‘My – throat?’ She had been dreading this moment for days, but she had never imagined they would take blood from there.

‘To best preserve its potency, your healing blood has to be taken fast. And the carotid artery is the fastest.’

‘Why not take it directly from my heart?’ Tali snapped. ‘That’d be even quicker.’

The old healer’s pouched eyes double-blinked at her. ‘I don’t like the treacherous Pale, Thalalie vi Torgrist, and I don’t like you. It’s a great honour to serve your country this way. Why can’t you see that?’

‘I don’t see you giving up your life’s blood.’

‘If my blood had healing powers, I would do so gladly, but I can only heal with my hands.’ Dibly studied her fingers. The knuckles were swollen and her fingers moved stiffly.

‘You’re not a healer, Madam Dribbly, you’re a butcher. Are you making blood pudding from my left-overs? If it heals so well, you could live forever on it.’

‘Bare – your – throat!’

It wasn’t wise to make an enemy out of one so exalted, who was, in any case, following the orders of the chancellor. But Tali had to fight. Robbed of her friends, her quest, and the man she had only realised she loved when he had been condemned in front of her, resistance was all she had left. She didn’t even have the use of her magery. Afraid that Lyf would lock onto it and track her down, she had buried her gift so deeply that she could not find it again.

Resistance was useless here. If she did not obey, Dibly would call her attendants and they would not be gentle. Tali took off her jacket and unfastened her high-collared blouse, her cold fingers fumbling with the buttons. She pulled it down over her shoulders, then lay back on the camp stretcher, shivering.

The chancellor’s cavalcade had fled the ruins of Caulderon three days ago, using powerful magery to cover their tracks. Now they were high in the Crowbung Range, heading west, travelling at night by secret paths and hiding by day. It had been cold enough in Caulderon, but at this altitude winter was so bitter that everyone slept fully clothed. Tali had not bathed since they left, and itched all over. Even as a slave in Cython, she had bathed every day. Going without one all this time was torment.

Madam Dibly passed a broad strap across Tali’s forehead and pulled it tight.

‘What’s that for?’ Tali cried.

Straps were passed around both her arms, above the elbows, then Dibly waved a cannula, large enough to take blood from a whale, in Tali’s face. The slanted steel tip winked at her in the lantern light.

‘Were you to move or twitch with this deep in your throat,’ the healer said with the ghoulish relish peculiar to her profession, ‘it might go ill for you.’

‘Not if you know your job,’ Tali said coldly.

‘I do. That’s why I’m strapping you down. And if you curb your insolence I might even unstrap you afterwards.’

The healer set a pyramid-shaped bottle, made from green glass, on the floor. It looked as though it would hold a quart. So much? Tali thought. Can I live if they take all that? Does the chancellor care if I don’t?

Dibly crushed a head of garlic and rubbed the reeking pulp all over her palms and fingers to disinfect them. Tali’s stomach heaved. The smell reminded her of her years of slavery in the toadstool grottoes. One of the most common toadstools grown there had smelled powerfully of garlic.

The collapsed vessel of a boar’s artery ran from the cannula to the bottle. Madam Dibly inspected the point of the cannula and wiped Tali’s throat with a paste of crushed garlic and rosemary. She could feel her pulse ticking there.

Why did her blood heal? Was it because she was Pale and had spent her whole life in Cython? If so, her healing blood was not rare at all – all eighty-five thousand Pale could share it. Or was there more to it? Did it have anything to do with the master pearl in her head? The missing fifth ebony pearl that everyone wanted so desperately?

‘Steady now,’ said Dibly.

The cannula looked like a harpoon. The old healer’s snaggly teeth were bared, yet there was a twinkle in her colourless eyes that Tali did not like at all. She was taking far too much pleasure in what she was about to do.

‘W-will it hurt?’ said Tali.

‘My patients never stop whining and squealing, but it isn’t real pain. It’s just fear of the needle and the moment you overcome that it won’t hurt at all.’

‘Why don’t we swap places?’ said Tali. ‘Bare your grimy, wattled old neck and I’ll stab the cannula into it up to the hilt, and we’ll see how pig-like your squeals are.’

Madam Dibly ground her yellow teeth, then in a single, precise movement thrust the cannula through Tali’s carotid artery and down it for a good three inches.

Tali screamed. It felt as though her throat had been penetrated by a spike of glacial ice. For some seconds her blood seemed to stop flowing, as if it had frozen solid. Then it resumed, though it all appeared to be flowing down the boar’s artery, dilating it and colouring it scarlet, then pouring into the green glass bottle.

It was already an inch deep. The watching healer separated into two fuzzy images and Tali’s head seemed to be revolving independently of her body, a sickening feeling that made her worry about throwing up. What would happen if she did while that great hollow spike ran down her artery? Would it tear out the other side? Not even Dibly could save her then.

Tali’s vision blurred until all she could see was a uniform brown. Her senses disconnected save for the freezing feeling in her neck and a tick, tick, tick as her lifeblood drained away –

The brownness was blown into banners like smog before the wind and she saw him. Her enemy, Lyf! She shivered. He was feeling in a crevice in the wall. She cried out, involuntarily, for he was in a chamber that looked eerily like the cellar where the eight-year-old Tali had seen her mother murdered for her ebony pearl. It had the samedomed shape, not unlike a skull …

It was the murder cellar, though everything had been removed and every surface scrubbed back to expose the bare stone of the ceiling and walls. Before being profaned by treachery and murder, this chamber had been one of the oldest and most sacred places in ancient Cythe – the private temple of the kings.

What was Lyf doing? He was alone save for a group of greybeard ghosts – Tali recognised some of them from the ancestor’s gallery he had created for himself long ago in the wrythen’s caverns. Lyf had a furtive air, lifting stones up and putting them down, and checking over his shoulder as though afraid he was being watched.

‘Hurry!’ said a spectre so ancient that he had faded to a transparent wisp, though his voice was strong and urgent. ‘The key must be found. Without it, all you’ve done is nothing.’

What key could be so vital that without it everything Lyf had done – saving his people and capturing the great city at the heart of Hightspall – was as nothing? And who was this ancient spectre who was telling the king what to do?

But the blood-loss vision faded and she saw nothing more.

But the next time Dibly took blood, Tali was going to find out.

*

‘You shouldn’t bait her, Tali. Madam Dibly is just doing what I ordered her to.’

Tali was so weak that she could not open her eyes, but she recognised the voice coming from the folding chair beside the camp bed. The chancellor.

‘Ugh!’ she said.

She tried to form words but they would not come, and that frightened her. She had been robbed of far more than the two pints of blood. She was enslaved again, worse than she had endured in Cython. There she’d had a degree of freedom, and vigorous health.

But the chancellor was using her like a prized cow – she was fed and looked after to ensure she could be milked of the maximum amount of blood. And once her body gave out, would she be discarded like a milkless cow?

There was also Rannilt to consider. If the blood-taking could weaken Tali so drastically, what must it be doing to the skinny little child, who had been near death only days ago?

‘You can stop all this,’ said the chancellor. For such a small, ugly, hunchbacked man, his voice was surprisingly deep and authoritative.

‘How?’ she managed to whisper.

Her eyes fluttered open. She was in his tent, the largest of all, and she saw the shadow of a guard outside the flap. The man was not needed. Tali lacked the strength to raise her head. The side of her neck throbbed. She felt bruised from shoulder bone to ear.

‘I know you’re holding out on me,’ said the chancellor. ‘Tell me what I need to know and I’ll order Madam Dibly to stop.’

Had Tali not been so weak, she might have given her secret away. If he guessed that she hosted the fifth pearl inside her, the master pearl that could magnify his chief magian’s wizardry tenfold, how could the chancellor resist cutting it out?

Hightspall was losing the war because its magery had dwindled drastically over the centuries. With the master pearl the chancellor could have it back. With the master pearl, his adepts might even command the four pearls that Lyf held. He might win the war, and even undo some of the harm Lyf’s corrupt sorcery had done to Hightspall. Such as the shifters that Lyf had created for one purpose only – to spread terror and ruin throughout the land, and turn good people into ravening monsters like themselves.

Like Tobry, her first and only love, turned into the kind of beast he had dreaded becoming all his life. But Tobry’s suffering was over.

Should she give up the master pearl? It wasn’t that simple. Ebony pearls could not be used properly within – or by – the women who hosted them. They had to be cut out and healed in the host’s blood, though this was fatal. Tali could only give up the pearl by sacrificing her own life.

Someone nobler than her might have made that sacrifice for her country, but Tali could not. Before escaping from Cython she had sworn a binding blood-oath, and until she had fulfilled it she did not have the freedom to consider any other course.

‘Don’t know – what you’re talking about,’ she said at last.

‘You’re lying,’ said the chancellor. ‘But I can wait.’

‘And you’re a failure.’ She wanted to hurt him the way he had hurt her. ‘You’ve lost the centre of Hightspall and you’re losing the war.’

He winced. ‘I admit it, though only to you. According to my spies, Lyf is already tearing down Caulderon, the greatest city in the known world, and rounding up a long list of enemies.’

She hadn’t thought of that. ‘What’s he going to do to them?’

‘Put them to death, of course.’

‘But that’s evil!’

The chancellor sighed. ‘No, just practical. It’s what you do when you capture a city – you hunt down the troublemakers and make sure they can’t cause any trouble.’

‘Does that include Rix?’ said Tali.

‘I’m told he’s number one on Lyf’s list.’ The chancellor smiled wryly. ‘I feel a little hurt – why aren’t I on top?’

‘I wish you were!’ she snapped, then added, ‘I couldn’t bear it if Rix was killed as well.’

Though the chancellor despised Rix, he had the decency not to show it this time. ‘He’s a resourceful man. He could have escaped.’

‘You chopped his hand off!’ she said furiously. ‘How’s he supposed to fight without a right hand?’

‘To escape a besieged city you need to avoid attention, not attract it.’

After a lengthy pause, he continued as though her problems, her tragedies, were irrelevant. Which, to him, they were.

‘The enemy hold all of central Hightspall – the wealthy, fertile part. Now I’m limping like a three-legged hound to the fringes. But where am I to go, Tali, when the ice sheets are closing around the land from three sides? What am I to do?’

This was the strangest aspect of their relationship. One minute he was the ruthless master and she the helpless victim, the next he was confiding in her and seeking her advice as though she were the one true friend he had.

The chancellor was not, and could never be, her friend. He was a ruthless man who surrounded himself in surreal, twisted artworks, and with beautiful young women he never laid a finger on. He was not a kind man, nor even a good one, but he had two virtues: he held to his word and he loved his country. He would do almost anything, sacrifice almost anyone, to save it, and if she wasn’t strong enough, if she didn’t fight him all the way, he would sacrifice her too.

He had ordered Tobry hurled off the tower to his death. He had maimed and condemned Rix, and enslaved her. Tali took a grim pleasure in every little thing she could do to defy him.

‘Where are you running to, chancellor, with your tail between your crooked little legs?’

His smile was crooked, too. ‘I’ve been insulted by the best in the land. Do you think your second-rate jibes can scratch my corrugated hide?’

Tali slumped. Five minutes of verbal jousting was all she could manage.

‘Is all lost, then?’ she said faintly.

He took her hand, which was even more surprising. The chancellor was not given to touching.

‘Not yet, but it could soon be. I fear the worst, Tali, I’m not afraid to tell you. If you know anything that can help us, anything at all …’

She had to distract him from that line of thought. ‘Do you have a plan? For the war, I mean?’

‘Rebuild my army and forge alliances, so when the time comes …’

‘For a bold stroke?’

‘Or a last desperate gamble. Possibly using you.’

Tali froze. Did he know about the ebony pearl? She turned to the brazier, afraid that her eyes would give her away.

‘You gave me your word,’ he went on.

Not her pearl. Worse. He was referring to the promise he had forced out of her in his red palace, in Caulderon. That one day he might ask her to do the impossible, and steal into Cython to rouse the Pale to rebellion.

She did not consider the promise binding, since it had been given under duress. But the blood-oath she had sworn before escaping from Cython was binding, and it amounted to the same thing. With Cython depopulated because most of its troops had marched out to war, the vast numbers of Pale slaves there were a threat at the heart of Lyf’s empire.

Sooner or later, he would decide to deal with the threat, and that was where Tali’s blood oath came in. She had sworn to do whatever it took to save her people. But before she could hope to, she would have to overcome her darkest fear – a return to slavery.