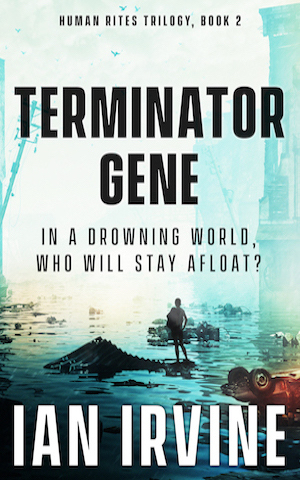

Book 2: Human Rites Trilogy

Jemma was at the window again, plucking at the gold ring on a chain around her neck. She looked pale, frightened and old.

‘Irith?’ she said, yet again.

Irith looked up from her reader, wishing it was a real printed book as they’d had in the good old days before the sea level rose six metres, flooded half the cities of the world and wrecked the world’s economy. No one had done anything about global warming until it was too late; now everyone was paying for it.

‘Yes, Mum?’ she said. Her mother had been on edge for months but would not say what was the matter.

Jemma went into the kitchen. Irith sighed and blanked the screen. Laying the reader on the table, she went to the window. She was small, like her mother, though more slender. Her hair was bound into an austere plait and she wore no make-up, for her mother discouraged self-absorption.

‘Beauty is like a dead dog by the side of the road,’ Jemma was fond of saying. ‘It attracts only vultures, hyenas and maggots.’

Seven floors below, an unmarked van pulled up outside the entrance and four people got out, dressed identically. Security! Irith suppressed an urge to duck out of sight – she’d done nothing wrong and had nothing to hide.

‘The kettle’s boiling, Mum.’

‘Mmm,’ said Jemma, but didn’t turn it off, which was unprecedented, given how obsessive she was about waste. The global sea-level emergency had flooded hundreds of coastal cities; trillions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure had had to be replaced and five hundred million people resettled. Taxes were sky-high and waste was a serious crime.

The officers were staring at the kitchen window. Irith shook herself and turned away. ‘Mum? There’s a Security van outside. I’ve never –’

Jemma’s mug smashed on the tiles. Irith ran into the kitchen. The kettle was still boiling and she turned it off. Once the ration had been used there was no more gas until the next month.

‘Mum? What’s the matter?’

‘He’s come for me. I knew he would.’

‘Mum?’ Irith gripped Jemma by her small shoulders.

Jemma was like a rabbit frozen in the headlights, and now Irith heard boots thumping up the stairs. Lifts were banned in buildings less than fifteen storeys high, to save energy.

‘Irith,’ Jemma whispered, controlling herself with an effort. ‘I’ve done all I could to prepare you. You’re fit, resourceful –’

‘Mum, please!’

‘Promise me you’ll keep out of this.’

‘No! Tell me what the matter is.’

‘You can’t do anything for me.’ Jemma’s hands caught at Irith’s wrists. ‘Give me your word.’ Her face was cracking at the seams.

Irith went cold inside, but said, ‘I’ll keep out of it.’

‘Promise?’

‘Yes,’ Irith lied. I’ll get you out of this, Mum, whatever it takes. ‘What’s going on?’

They were in the corridor now, the footsteps like a slow drumbeat. Irith followed her mother into the living room. She was staring at the door.

‘It’s Per Lindstrom …’

He was the President of the Global Congress, which had been formed to try and save the world from unstoppable global warming. It was not quite a world government since Britain had led a minor withdrawal two years ago, but almost. ‘What’s he got to do with you, Mum?’

The front door was smashed open and two women and two men pushed inside, dressed in steel grey. The leader, a big woman with a bosom like an opera singer, was not armed, but Security did not need to be.

‘Jemma Hardey?’ The leader had a jaw as round as a melon and eyes like sapphires stuck in scoops of butter.

Jemma was eerily calm now. ‘How may I help you?’

‘Come with us.’

‘I’ll get my bag.’

‘Stay where you are.’

The other woman marched into Jemma’s bedroom. The men unpacked a scanner and the taller fellow, who had a badly repaired hare lip, walked around the room, passing an array of sensors back and forth. The other man searched the cupboards.

‘What’s going on, Mum?’ said Irith.

‘They’re taking me away.’ Jemma’s face was expressionless, though her fingers were squirming in her pockets. ‘For something that happened a long time ago.’

‘Silence!’ snapped the leader, poking Irith in the chest with a finger as hard as pig-iron. ‘You are Irith Hardey?’

‘Yes,’ said Irith, swallowing.

‘You have completed your course of study?’

‘After I defend my honours thesis, next Wednesday.’ Six days away.

‘You may shelter here until that is done. Then you have one day to remove your possessions.’ She used the word like an oath.

Jemma spun around. ‘But this is my flat! I own it outright.’

The woman was inexorable. ‘You own nothing. All your possessions are forfeit. Your daughter will be allocated dormitory accommodation.’

‘But I need my privacy …’ said Irith. The idea of sleeping in a cramped, airless room with dozens of women, all dissecting her mother and taking pleasure in her fall, was unendurable.

‘Aren’t we the privileged one!’ sneered the leader.

It had not always been this way. Before global warming melted the ice and the seas rose, before the Global Congress made consumption a sin and every human pleasure a crime, her country had been a cheerful, outward-looking place. Now it seethed with envy and malice.

Irith felt sick. ‘You can’t do this. We know our rights.’

‘The warrant is signed by the President of the Global Congress –’

Per Lindstrom again. ‘Why?’ Irith broke in.

‘You have no right to ask.’ The woman recited from a reader, ‘Detention without trial and confiscation of property are legitimate measures where there is a genuine threat to national security.’

‘How can my mother be a threat to national security?’ Irith snapped.

The tall man knocked her down from behind and put his size-fourteen boot on her back.

‘That’s what we’d like to know,’ said the bosomy woman. ‘And if you don’t desist, you will also be charged.’

Irith, though dazed from the blow, tried to get up. Jemma shook her head. Stop. You can’t do anything.

Irith watched numbly while her home was scanned – walls, floor and ceiling. They copied everything on her laptop and boxed up all the books, files and papers in the house. The second woman came out of Jemma’s bedroom carrying a bag.

‘Come,’ said the first officer, jerking Jemma by the arm.

She broke free, ran three steps and threw her arms around Irith. ‘I’m sorry. I should have told you.’ She hugged Irith tightly. Two fingers slipped inside the collar of Irith’s shirt and something fell down her back, then the two men dragged Jemma out.

Irith followed them down the stairs and stood outside, watching as they took her mother away.

Eventually she realised that people were walking around her, keeping well clear, as if mere contact could taint them, too.

Rainwater trickled down her forehead. She wiped her face, then ran up the stairs. Jemma had taught her to be resourceful; Irith had trained in self-defence, excelled in the rifle club, and had been on many self-reliance courses. She had to do something.

After picking up the scattered pieces of the door lock, she propped the door closed with a chair and went into her room. Each birthday since she’d turned five, Irith and Jemma had marked the annual sea level rise on her bedroom doorway, the way normal parents would have marked a child’s height. It was a link to her father, Ryn, who had died days after she was born. He had been a scientist studying the melting of the Antarctic ice sheets and, perhaps because of him, Irith loved the sea.

Jemma had taken her to the beach once, when she was little, but all the beaches were submerged now and it would take centuries for new ones to form.

Jemma and Ryn had been involved, in a minor way, in the events that had led to the formation of the Global Congress twenty-one years ago. Was that why she had been arrested? Why now, after all this time?

Irith untucked her shirt and pulled Jemma’s note out. It was scrawled on a fragment of coarse paper, the kind that had once been used for newspaper, and said but three words, ‘Call Levi Seth’.

Irith knew the name. He was an old friend of Jemma’s, which was notable in itself, for her mother had few friends. Jemma had been to see Levi several times in the past months, and Irith had wondered if they were having an affair.

She went to the screen in the corner and sat at the keyboard, but her hands froze above the keys. Security could be monitoring everything she said, everything that passed across the net. But she had to know.

Before she could type Levi’s name, the power went off. Electricity was rationed and the power would not come back on until 6 pm. She went out to the university, logged on in the library with a supposedly untraceable cashcard, searched the directory for Levi Seth, and called.

A middle-aged, bald man with heavy-rimmed glasses answered. He was Indian, she judged, from the name.

‘Hello?’ he said.

She pressed the image button so he could see her face. ‘My name is Irith Hardey –’

‘Stay there!’ The screen went blank and the dial tone sounded, followed by a series of clicks.

Was he a friend or an enemy? There was no way to tell. Opening her reader, she paged through her thesis. The oral examination could be brutal and she needed to be prepared for any question, but it was impossible to concentrate. What did they want Jemma for? Irith knew of people being taken away by Security, though she had never heard of their property being confiscated. It made her realise just how alone she was, and how helpless.

She searched for recent footage of President Lindstrom, but found only one interview, for an obscure program that was long defunct.

He was a very tall man, long in the legs and short in the body, with a gritty, compelling voice and a scorching stare. His walk was peculiar – head, shoulders and torso sloping back like the tower at Pisa, arms swinging, legs snapping.

In the interview, he was hectoring the interviewer about an ecological collapse in Central Asia, swaying as he spoke. His fingers moved constantly and his left foot jerked this way and that.

‘It’s just a small area,’ said the interviewer, ‘only a few species threatened. I don’t see the problem –’

Lindstrom sprang up. ‘Humanity is the problem!’ he roared, pointing a long finger that shook in his sudden rage. ‘Too much humanity, too greedy, too –’ His larynx bobbed up and down and he seemed to be having difficulty swallowing. ‘Too selfish and too stupid. You’re off the air, for life.’

He stalked out, leaving the interviewer staring after him, corpse-faced.

So that’s what we’re dealing with, Irith thought, staring at the blank screen. That’s who’s taken Mum. And he’s the most powerful man on Earth.

CHAPTER TWO

‘You don’t look much like your mother,’ said a soft voice.

Irith whirled. The man was in his fifties, slim and dark, with saggy ears and a bald skull fringed by fluffy grey hair. His eyes looked kind, though.

‘I’m Levi Seth.’ He held out his hand.

‘Irith.’ She shook it. His grip was surprisingly firm.

‘Shame about the cricket.’

England had just thrashed Australia in the Fifth Test, as they had in the previous four. It was only the second five–nil defeat in a hundred and fifty years. ‘I used to watch it when I was a kid,’ said Irith. ‘It – it was a link with Dad. Did you know him?’

‘I met him a few times. Let’s go for a walk.’

They went out the front door of the library, crossed the road and headed across the lawn. Levi settled on a low wall in front of the Great Hall, looking down towards the park and the main gates of the university, and checked all around.

‘What happened?’

‘Security took Mum.’

‘When?’

‘This morning, and our flat has been confiscated.’

He stiffened. ‘That’s bad!’

‘What’s going on? She said something about Lindstrom.’

He rose and she did too. His face was carefully expressionless as he paced beside her. ‘What did she say?’

‘Just his name. You know what it’s about, don’t you?’

He sighed. ‘Yes.’

‘Please, Levi. Mum is all I’ve got.’

‘My former partner was just your age when she became involved in this business. It destroyed her.’

That did not help. ‘I’m already involved.’

He looked over his shoulder at the clock tower. Checking for cameras, she supposed.

Levi took her arm and they strolled down towards a stand of ancient, spreading figs near the gates. He stopped between the trees, on a groundcover of ivy, out of sight of the buildings. ‘Before you were born, a fanatical environmental terrorist called Ulf Bamert believed that the only way to save the planet was to eliminate humanity, and he set out to do just that.’

‘What happened to him?’

‘He was supposed to have burned to death twenty-two years ago.’

‘Before I was born?’

‘Yes. But Jemma believes that he didn’t die. She thinks he had a face transplant and continued with his plan and, a few years back, became President of the Global Congress.’

‘Why has he taken Mum?’

‘Revenge. Jemma and I helped to thwart him a long time ago, and he’s not a man to forget.’

Instinctively, Irith clutched at his arm. ‘Then you’re in danger too.’

‘I … used to be an expert in systems protection, and systems breaking, but I covered my tracks pretty well. But that doesn’t help if they torture the truth out of one’s friends.’

‘They’re going to torture Jemma?’ It came out louder than she’d intended. A man sitting on a bench across the road looked around, though he was careful not to make eye contact.

‘Shh! They may be watching now.’ He led her deeper into the trees.

Irith felt a flood of panic and an overwhelming urge to run away, but forced herself to walk calmly.

‘What did you and Mum do back then?’

‘It’s now that matters, and now is a very dangerous time, with all the riots –’

She stopped abruptly, ankle-deep in the ivy. ‘What riots?’

‘About overpopulation and compulsory sterilisation. It’s not on the public net, but there have been sterilisation riots in a dozen countries, brutally put down. Now the religious right in the United States has almost enough votes to force secession from the Global Congress, as Britain did a while ago, and if they do things could get rather bloody. Lindstrom isn’t a man for turning.’

They walked on, crossed the road and Levi stopped on the other side. ‘What are you going to do?’ Irith said.

‘I’ll have to disappear.’

‘What about me?’

‘It’ll be tough, but you’re not in any danger.’

‘Is there anything I can do for Mum?’

‘It’s too late. I must go, Irith. Thank you for warning me.’ He shook her hand and turned down the drive towards the main gates.

‘But I thought you were going to help me,’ she whispered.

*

Irith spent the following day trying to find out what had happened to Jemma, but the response was always the same.

The official would be politely interested until she gave her mother’s name, when there would be a flurry at the keyboard and the face would go blank. ‘I’m sorry, there is nothing I can do for you.’

‘Can you tell me who I should talk to?’ she said desperately.

‘I’m sorry, there is nothing I can do for you.’

She tried to call Levi again but he did not answer, and his name was no longer in any public directory. Had they taken him too?

Irith went to the library, studied until dark, then headed home.

The late news contained only one item of note.

In the Vatican today, Pope Joan announced that she planned to sell the remaining treasures from the Vatican Museum in a last-ditch attempt to stave off bankruptcy, and to refocus the Church on the needy. ‘In this age of austerity and deprivation,’ she said, ‘the Church cannot justify the accumulation of gilded treasures.’

The news attracted little interest in an increasingly secular Europe. However, in fundamentalist America, the announcement was greeted with fury and calls to excommunicate Pope Joan.

*

Wednesday came, and Irith submitted to the ordeal of her oral examination. It went better than she had expected, although the external examiners were as formal as automatons. At the end they did, however, congratulate her on a fine piece of research.

Irith thanked them and walked home through the driving rain. She’d planned a celebration dinner with her friends but that seemed pointless now. Besides, she had to be out tomorrow and she had not packed.

Jemma had proudly bound Irith’s personal copy of her thesis in leather – a proper, old-fashioned book – but she could no longer see the point to it. She put it in a box, along with her academic record – eight high distinctions, one distinction. She’d once fretted about that miserable distinction spoiling her perfect academic record, but only students cared about such trivial things.

The only thing that mattered was to free her mother and Irith was going to find a way. Once she started something, she never gave up. She tried to think of ways and means as she packed, but she had led a studious life and had no idea where to begin.

Hours later, she checked her watch. The power would be back on and, needing a distraction, she turned on the screen. Power was heavily rationed and inspectors could appear at any time to check if illegal appliances were being used. The punishment for a first offence was confiscation of the appliances and a month without power. For a second offence, disconnection for a year. Nobody offended a third time.

Sitting back in the armchair, she closed her eyes. She didn’t want to think about tomorrow …

Jerked awake by a familiar voice, she looked around in confusion. ‘Mum?’ She was running for the door when she realised that Jemma’s voice was coming from the screen.

‘Welcome to the first edition of the President’s Page, the personal view of Congress President Per Lindstrom. I’m Jemma Hardey.

‘Today I’ll be talking about the worsening population crisis and what each of us can do about it. Despite universal contraception, selfish people continue to evade their birth-control responsibilities, and overpopulation is eating the world alive. Implant removal has reached epidemic proportions.’

Jemma looked up at the camera and, fleetingly, a sick horror showed in her eyes, but it vanished and she was the stern professional again.

‘Population criminals will be punished severely, though why should this be necessary? Parents, give your children the ultimate gift – sterilise them at birth. They’ll never miss what they do not have –’

Irith, sickened, turned it off. Jemma loved children. How had they coerced her to say such an evil thing? They must have threatened to harm Irith.

And, presumably, they were going to.