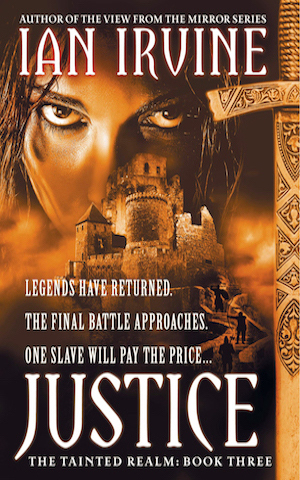

Book 3: The Tainted Realm

PART ONE – INCARNATE

CHAPTER 1

Tali was holding the disembowelling knife so tightly that her knuckles ached. She looked into the eyes of the man she loved, the man she had to kill, and her heart gave a convulsive lurch. She tried to swallow but her throat was too tight.

‘It has to be done,’ said Rix dully. ‘It’s the only way.’

‘That doesn’t make it any easier.’

It was ten minutes past dawn and they were in a meadow by a pebble-bottomed stream, a pretty, peaceful place. A band of ancient trees clothed each bank, forming a winding green ribbon across the surrounding grassland. White flowers dotted the short meadow grass; in the distance, a range of snowy mountains ran from left to right. Behind them, on the plain beyond a low hill, four armies prepared for slaughter.

Their mad, ruined friend Tobry was chained to the largest tree, its trunk two yards through the middle. His shirt had been torn open, revealing a trace of reddish fur on his chest. His eyes were caitsthe yellow, the mark of the incurable shifter curse. To Tali’s left a brazier blazed; beside it sat a paper-wrapped packet of powdered lead. The one sure way to kill a caitsthe was to burn its twin livers on a fire fuelled with that deadly substance.

‘Now!’ said Rix.

‘I thought he’d died three months ago,’ Tali said softly, putting off the evil moment.

‘We saw him thrown from the tower.’

‘I ached for Tobry, wept for him.’ She slipped her fingers into her short hair, caught a handful and clenched until her scalp stung. ‘And finally, I came to accept his death. Then he came back as a shifter, doomed to madness …’

‘There was nothing to be done. No one’s ever cured a full-blown shifter.’

‘He told me to turn away.’ Her voice went shrill. She moved closer to Rix. ‘Tobry knew he’d die a mindless beast, and I couldn’t accept it. ’ Tali’s pale skin flushed to the roots of her golden blonde hair. ‘I did shameful things, trying to save him. Wicked things …’

‘Out of love,’ said Rix uncomfortably.

He thrust his sword into the soft ground, bisecting a white daisy, and stepped away, scrubbing his dead hand across his eyes.

Tali looked up at Rix – she was a small woman and he stood head and shoulders above her. ‘He doesn’t know us; he’ll kill us if he gets the chance. He’s got to be put down and I … just … can’t … bear … it.’

He put his good arm around her shoulders. The shifter snarled. Rix pulled away and, with a jerky movement, plucked his sword from the grass.

‘He’s a beast in torment. We have to do our duty by him.’

‘Yes,’ said Tali.

‘Ready?’ Rix’s jaw locked.

‘Yes,’ she whispered.

‘It’s hard to kill a shifter.’

‘I know.’

‘When I strike it’ll probably turn him, and in caitsthe form he’ll be three times stronger. A caitsthe can heal most injuries in seconds by partial shifting. You’ll have to be quick.’

‘I know.’ Tali’s fingers tightened around the hilt of the knife. She rubbed her knuckles with her left hand.

‘Cut straight across the belly, left to right, then heave out –’

‘Get on with it!’ she screeched.

Rix swallowed audibly, rubbed a large signet ring on his middle finger, then raised the sword in a trembling hand. But before he could strike, someone came belting through the trees towards them. A pale, skinny girl, about nine.

‘Stop!’ she screamed. ‘I can heal him.’

‘Not in front of Rannilt,’ Tali hissed.

‘What kind of a man do you think I am?’ Rix snapped.

Tali dropped the knife and ran to grab Rannilt. Even chained, Tobry was too powerful, too dangerous. Rannilt stopped.

‘You can’t heal anyone,’ said Tali, spreading her arms wide. ‘You lost your healing gift when Lyf attacked you in the caves that day. He stole your magery, remember?’

‘He didn’t, he didn’t!’ cried Rannilt. ‘You’re lyin’.’

She darted around Tali, under Rix’s outstretched arm, and ran towards Tobry.

‘Stop her!’ said Tali.

Rannilt, a little, waiflike figure, reached out to Tobry. Her arms were scarred, her skinny fingers crooked from having been broken repeatedly when she’d been a bullied slave girl.

‘I can heal you,’ Rannilt said softly, standing on tiptoes and gazing earnestly up at Tobry. The air between them seemed to smoulder. ‘I got to heal.’

Tobry made a small, yearning movement, as if allowing her to try, but came up against the chains and let out a roar. Rannilt jumped backwards, her thin chest heaving. After a few seconds she took a small step towards him.

‘You got to let me try,’ she said to Tali. ‘Tobry’s my friend.’

‘No one can heal him,’ said Tali. ‘Rix, grab her.’

Rix sprang and tried to drag Rannilt away. She kicked him in the shins, drove her bony shoulder hard into Tali’s breast, knocking her off her feet, and ducked past.

‘You’re not killin’ him!’

Rannilt shoved the brazier over, scattering coals across the ground, then took hold of the packet of powdered lead and tries to tear it open. The tough paper did not give. She took it between her sharp little teeth.

‘Put that down!’ roared Rix. ‘It’s deadly poison.’

Rannilt spun on one foot and hurled the packet against a rock. It burst open, scattering lead dust everywhere.

‘You’re not murderin’ Tobry,’ she shrieked.

The ground shook so violently that she fell to one knee. The quakes and tremors had been coming for days now but this one seemed different. Stronger. Tali turned to Rix.

‘Was that –’

‘The Big One?’

The land heaved and a crack opened fifty yards away, squirting dust into the air like a fountain. Rannilt let out a squawk.

The earth gave forth an enormous, grinding groan. A wave passed through the ground, tossing the three of them off their feet. A larger wave followed, and a third, larger still. Tali was thrown backwards across the grass; her head cracked against a stone and dust filled her eyes and nose. A series of wrenching roars were followed by ground-shaking thumps. She opened her eyes but could not see.

The earth groaned like a giant in torment. Rannilt screamed and bolted.

Rix roared, ‘Look out!’

He heaved Tali into the air, carried her for four or five long strides, then dived with her as the ground shuddered one final time. There came a colossal, thundering crash.

She wiped dust out of her eyes and looked around. Rix was on his knees a couple of yards away, gasping. Many of the trees along the stream had been toppled.

‘That was too close,’ he said.

She sensed something behind them – huge, blocking the morning light. Tali turned slowly. The gigantic tree had been wrenched out by the roots and its trunk lay in a deep indentation in the soft ground only a few yards from her. Tobry’s chains ran around the trunk and disappeared below it. The crown of the tree had been smashed and broken branches were scattered across a large area. Bees buzzed frantically around a dislodged hive. Rannilt was nowhere to be seen.

Tali wrapped her arms around herself and stared at the fatal spot. It had been so quick. She sagged.

‘Do you think, even a shifter –?’ she began, not looking at Rix. She was afraid to see the truth in his eyes.

‘No,’ said Rix. ‘No chance at all.’

An ache formed in her middle, a vast upwelling of loss that spread all through her. Her eyes stung. ‘It’s for the best, isn’t it?’ But she wanted to scream and pound her fists into the dirt.

‘He wouldn’t have felt a thing.’

Rix took her right hand with his good hand. It enveloped hers completely. They bowed their heads for a minute, remembering Tobry as he had been before the shifter curse took him.

Rannilt! ‘Where’s Rannilt?’ Tali pulled free, ran the length of the fallen trunk and clambered onto the highest branch, staring around her. Her voice rose. ‘Rix, I can’t see her.’

‘She’s safe.’

‘How do you know?’

‘She ran that way as the tree fell.’ He pointed west across the grassland.

‘I’ll go after her …’

But Tali slid down and plodded back to Tobry’s chains. Her legs felt so heavy it was an effort to walk. She stared at the chains as if her gaze could penetrate the ground to the body beneath. Her eyes filled with tears. She wiped them away. ‘You’d better get going – you’ve got an army to command.’

Rix swallowed. ‘Assuming I can. I’ve never led more than fifty men before – and that ended in disaster.’

‘Rubbish! You led hundreds of people when Garramide was besieged – you saved the fortress.’

‘It’s not the same as leading an army of five thousand into battle.’

Before the chancellor died, last night, he had outraged his generals by giving the command of Hightspall’s army to Rix.

‘The chancellor despised me for betraying my own mother,’ Rix went on. ‘And rightly so.’

‘You had no choice. She committed high treason – and murder.’

‘And yet, she was my mother,’ Rix said bitterly. He paced across the grass, then whirled. ‘Why did he give me the command?’

Tali knew that Rix had always been troubled by self-doubt. He had to pull himself together, fast. ‘You earned his respect. He believed you were the only man with a hope of leading our army to victory.’

‘Then he was a fool!’ Rix snapped. ‘Lyf’s army is fifty thousand strong. Axil Grandys has ten thousand hardened veterans, and a genius for leadership. All I have is five thousand men who’ve known only defeat … and three failed commanders who hate my guts.’

‘The Pale are on our side.’

‘Five thousand former slaves, mostly small, undernourished, untrained and poorly armed.’

‘I’m also Pale,’ said Tali softly. ‘Also small, undernourished and untrained.’

Rix managed a fleeting smile. ‘So you are – yet you led the slaves’ rebellion in Cython, and won their freedom. You’ve changed our world. I have to be just as positive.’

His grey right hand, from which he had gained the name Deadhand, twitched. He froze, his lips parted.

‘What is it?’ said Tali.

‘I dreamed about the portrait last night …’

‘The one you painted for your father’s Honouring?’

‘Yes …’

The portrait, which portrayed Lord Ricinus killing a wyverin – a winged beast like a two-legged dragon – had been intended to symbolise him vanquishing House Ricinus’s enemies. But sometimes Rix’s paintings held messages about the future, and the portrait had contained a hidden divination – that Rix’s father and his house would fall.

The Honouring had begun in triumph. House Ricinus had been raised to the First Circle – the greatest and oldest families in Hightspall. But the night had ended in disaster, with Lord and Lady Ricinus condemned to death by the chancellor for high treason, the fall of House Ricinus, and Rix utterly disgraced.

‘But in my dream the picture had changed,’ said Rix. ‘The wyverin was only pretending to be dead; it was rising to kill Father. And the Cythonians say …’

‘What?’ said Tali.

‘When the wyverin rises, the world ends.’

‘Whose world – ours, or theirs?’

‘I don’t know. But there’s more to the portrait than I ever intended. There’s something I’ve missed …’

***

CHAPTER 2

Leaving Tali to find Rannilt, Rix ran for the army camp, which was a mile and a half away on the other side of the hill. He had to get ready for a battle he couldn’t hope to win, yet had no option but to fight.

The sky had clouded over and a keen southerly drove scattered raindrops into his face. He reached the top of the hill, looked east towards his army, and stopped, panting. His stomach gave an anxious quiver. He rubbed his face with both hands, drew a deep breath and released it in a rush. What if he couldn’t do it?

The sacked generals undoubtedly resented him; they probably hated him. Rix could not guess how the troops felt, though every man would know he had betrayed his own mother. He’d had no choice – her conspiracy to have Hightspall’s chancellor assassinated in wartime was high treason, the blackest crime in the register.

And yet, and yet … his own mother …

Rix’s parents had died the cruel deaths ordained for traitors. Though the chancellor had spared Rix, he was forever tainted by their crimes and his own betrayal. In time the world might forget or forgive him, but Rix never would. It was too monstrous.

His stomach gave another flutter. He fought an urge to run the other way, and keep running. No, it was his duty to take command, to fight for his country and protect his troops. He had to find a way. He ran on, reached the camp and stopped, looking around in dismay.

The place was in chaos and the troops were milling around, leaderless; he couldn’t see an officer anywhere. The quakes had toppled hundreds of tents, several were on fire, and a steaming crevasse ran through the middle, a roaring fan-geyser gushing up from its centre for a good fifty feet. Drifting plumes of steam obscured the part of the camp that lay beyond.

To Rix’s left a fault scarp had lifted the ground by several feet. Further left, the pond from which the camp had drawn its water was an empty expanse of mud and dying eels, which the cooks were collecting in baskets. A hundred feet further on, a broad expanse of soil had liquefied to grey quick-mud. How the hell was he supposed to fight in country like this?

A weedy soldier slouched by, dragging a notched sword so blunt that he would have been hard pressed to cut an onion with it.

‘Hoy!’ said Rix.

The soldier ignored him.

‘You, dragging the sword, here!’

He turned towards Rix, disinterestedly. Either he did not recognise his new commanding officer or he was too ill-disciplined to care.

‘What news of the enemy?’ said Rix.

The soldier shrugged.

‘The Cythonians? Grandys’ army?’ said Rix.

‘No one tells us nothin’.’

Rix clenched his fist, thought better of it and thrust it in his pocket. ‘Get that sword sharpened.’

Where was he to start? He was looking vainly for a familiar face among the five thousand milling men when a meaty hand caught him by the left shoulder and jerked him around. General Libbens!

‘You’re a bastard, Deadhand!’ snarled the chancellor’s former general, who had led his army to a crushing defeat in Rutherin several months ago and blamed his officers for it. ‘A stinking traitor from a treasonous House, and you got only command by foul sorcery –’

Rix was used to this kind of abuse – he’d had it, one way or another, for months – though he wasn’t taking it from his officers.

‘I don’t know any sorcery. I couldn’t cast a spell to save my life.’ No, he must not sound apologetic. He had to take charge. ‘This camp is a shambles. Why haven’t you pulled the men into line?’

‘Our commanding officer was away, communing with a mad shifter.’

‘That’s why we have a chain of command, you incompetent fool. No wonder the chancellor sacked you. Put the camp to rights, now!’

Libbens’ red face darkened to a bruised purple. His right hand drifted towards the hilt of his sword.

‘Draw on your commander and you hang,’ Rix said coldly.

Judging by Libbens’ expression, he wanted to hack Rix’s head from his shoulders and mutilate his corpse; he wanted it so badly he was shaking. He stalked off, bellowing at his officers.

Spiders hunted one another down Rix’s spine. Then, from the far side of the camp, someone let out a long, agonised scream. A man’s scream, followed by a high-pitched whinnying.

He squinted through the drifting steam but could not see man or horse. The ground quivered and the injured man let out a shrill, bubbling shriek of agony. Rix pinpointed the direction and ran, dodging around the collapsed tents. He leapt a foot-wide crevasse; his feet sank ankle-deep in a patch of soft earth; he drove on and, twenty yards ahead, saw it.

A second crevasse, a great tear in the ground, three feet across at its widest and a couple of hundred yards long. A horse’s head and neck protruded out of it, thrashing back and forth. Rix could see the terror in its brown eyes. Half a dozen soldiers were standing around the crevasse, staring, though none made any attempt to help the trapped beast.

Rix skidded to a halt at the edge, leaned over, then sprang backwards. The crevasse cut through deep, crumbly soil and soft rock that could collapse at any moment. The horse was caught by the chest, trapped in a vertical position and kicking helplessly. One of its front legs was broken and it could not be saved. It would have to be put out of its agony.

‘Help!’ an unseen man groaned.

Rix went sideways until he could see past the horse. Two men were trapped further down, where the sides of the crevasse bulged in. The smaller fellow had blood around his mouth and nose, and the right side of his chest was bowed inwards as if the horse had kicked him. Broken ribs and a punctured lung, Rix judged – almost certainly a death sentence.

The ground shuddered and the horse kicked instinctively, thud. The man with the crushed chest let out another bubbling cry, fainter this time. The other man was supporting his right arm with his left, as if his collarbone was broken. With such an injury he had no chance of getting himself out.

‘Help! Please help.’

The desperate cry came from much further down. A shiver ran up the back of Rix’s neck as he peered into the shadowed depths. The crevasse widened below the bulge, then narrowed steadily as it went down, and far below he made out another three trapped soldiers. One fellow was alternately whimpering and moaning, a dreadful, hackle-raising sound. The second man was thrashing violently as if having a panic attack. The third soldier, the highest, made no sound, though the whites of his eyes were luminous in the gloom.

They were at least forty feet down. Rix’s throat clamped at the thought of being trapped in such a place, either starving to death or slowly suffocating when the soil fell in on them. Or, most horrible of all, being slowly squeezed to jelly as the crack closed again …

How was he to get the injured men out when they could not help themselves? He probed the edge of the crevasse with one foot. The soil cracked; it would not support his weight.

Dozens of soldiers were gathering along the crevasse. ‘Get me three sturdy poles,’ said Rix, ‘six inches through and at least ten feet long. No, make it twelve feet long. Plus a hundred and fifty feet of rope and a block and tackle.’

The soldiers looked past Rix, as if seeking confirmation of the order. Libbens was behind him, scowling. Libbens stamped a foot. The edge of the crevasse crumbled and he leapt backwards.

‘It’s not worth the risk,’ said Libbens. ‘Leave them.’

Rix fought down his fury. ‘You’re a coward as well as a fool, Libbens.’ He met the eyes of his troops. ‘I’m your commanding officer and the least of my men is worth the risk.’ He pointed to the nearest group of soldiers. ‘You! Fetch the gear, now.’

After a momentary hesitation, they ran. Libbens walked away, stiff with outrage. Rix paced the length of the crevasse, looking for a safer way to reach the trapped men, but there was none. The best way was straight down, here where it was widest, but first the crippled horse had to be put down and hauled out.

The man with the crushed chest let out another scream. Rix looked around. ‘I need a volunteer …’

The soldiers backed away. He cursed them under his breath. What kind of miserable army had he inherited?

‘Come back here!’ They returned, slowly. He took a deep breath, then roared, ‘Rope, now!’

A soldier came running with a coil of rope. Rix cut it in half and knotted an end of one length around his chest, under the arms. He pointed to the four most reliable-looking men, in turn, and tossed the coil to the nearest.

‘You four, take hold of the rope and hold tight. Don’t let it out until I tell you. Got it?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said the leading man.

Rix backed to the most solid edge he could see, four feet from the horse’s head. The ground began to crack underfoot. ‘Pay the rope out slowly as I go down. Don’t let me drop, all right?’

‘Yes, sir.’

He stepped backwards over the edge, creating a shower of earth, but as soon as his weight came on the rope he dropped sharply.

‘I said hold it!’ he bellowed.

He stopped, hanging in the middle of the crevasse, facing the trapped horse. It lowered its head to his level; it was panting and foam-covered strands of saliva hung from its mouth. A lump of earth thudded onto its back. Its eyes rolled and it kicked backwards, connecting with a pulpy thud. The soldier with the crushed chest made a gurgling sound. Rix winced.

He stroked down the horse’s long face. ‘Steady now,’ he said softly. ‘It’s all right. The pain will be over in a minute.’

It slowly quietened. Rix continued to stroke its nose and soothe it, feeling as though he was plotting the murder of a friend. Another friend, he thought grimly. He reached down, took his sword in his left hand and rotated on the rope. The job had to be done quickly, cleanly and as painlessly as possible, and that wasn’t going to be easy in this confined space.

‘Down, slowly!’ he said to the rope men. ‘Two feet.’

They dropped him four feet. Now he was well below the horse’s neck. The ground trembled and dirt and small stones showered down on him. The horse whinnied. One of the men trapped in the depths cried out in terror.

‘I’m sorry,’ Rix said to the noble beast.

With a quick, deep stroke, he cut its throat. Hot blood pumped out, gallons of it. He covered his face but there was nothing he could do to get out of the deluge; in seconds he was drenched. The horse thrashed its legs; its head rose and fell; it looked him in the eyes and he read betrayal there, then its head drooped.

‘Up!’ he yelled.

The soldiers raised him and he clambered out, dripping blood.

‘Don’t leave us!’ cried one of the trapped men.

‘I’m not going anywhere,’ Rix called down. ‘I’ll get you out.’ Or die in the attempt, more than likely.

The horse took a long time to die.

A dozen men came staggering up, bearing three heavy poles and the other gear.

‘Is anyone here a rigger?’ said Rix.

A stocky man with a red birthmark on his forehead stepped forward. ‘I am.’

‘Rig up a tripod and tie the block and tackle under the top. Then swing one leg of the tripod across until the block and tackle is above the horse.’ Rix tossed him the other length of rope. ‘Run it down to me.’

When it was ready Rix pulled the rope down from the block and tackle, and the soldiers lowered him down the blood-soaked crevasse. With some difficulty, he fastened the rope around the belly of the dead horse and, with a dozen men heaving, it was hauled out. He supposed the poor beast would end up on their dinner plates. An army could never get enough fresh meat.

He swung across to the two injured men. Astonishingly, the soldier with the crushed chest was still alive. He was shuddering with the pain, and every breath gurgled in his lungs as though they were partly filled with blood, but somehow he clung to life.

‘End – it,’ he gasped. ‘No hope now.’

Putting him out of his agony would have been the decent thing to do, but Rix couldn’t do it. Not in front of a hostile army he had to win over.

‘What’s your name, fellow?’

‘G-Gam. Common soldier.’

‘I’ll soon have you up, Gam,’ said Rix. ‘Then Holm will look after you. He’s the best surgeon I know.’ Though Rix doubted if even Holm could save a man with such injuries.

How to get him up? Rix couldn’t tie a rope around Gam’s crushed chest. He fashioned a harness around the soldier’s hips and Gam was lifted out, groaning piteously.

The haul rope came back down in a shower of grit. Rix fixed it to his own rope and swung across to the soldier with the broken collarbone, a hard-faced bruiser with two front teeth missing. And the soldier surprised him.

‘Tonklin’s the name, sir. Sergeant Tonklin, and they’re my men at the bottom. I’ll be all right for a while. Go down for them before the crack closes. ’

Rix’s scalp crawled. The ground was still quivering, and a larger quake could close it as easily as it had opened. He looked down at the trapped men and his right arm developed a tremor. He wanted out of this deadly crack, right now.

‘The blokes up top can haul me out any time,’ said Tonklin.

‘You’re a good man,’ said Rix. His guts throbbed. He forced himself to ignore the pain. ‘Lower me until I say stop,’ he called. ‘Steadily.’

They lowered him in a series of tooth-snapped jerks until, forty-five feet down, he was level with the highest of the three trapped soldiers. Though tall, he was a beardless boy of fifteen or sixteen, and his deep blue eyes were flicking wildly back and forth. He was biting his knuckles, fighting panic and the urge to scream. Rix knew how he felt. The crevasse had a malevolent feeling, as if it ached to crush them into oblivion, and the air reeked of the horse’s blood. Rix reeked even worse.

‘What’s your name, lad?’ he said.

‘Harin. And that’s Dessin.’ Harin indicated the lowest man, ten feet below them. ‘He’s my father, and he’s hurt bad. Can you –?’

‘I’ll get to him in a minute,’ said Rix. ‘You injured?’ He untied the haul rope and began to fasten it around the chest of the boy.

‘Just scratches. Please, look after father first.’

The ground shook, raining dirt down on their heads. The earth groaned and the crevasse narrowed several inches.

Dessin shrieked. ‘Pull me out! It’s crushing my legs!’

‘I’ll get to you shortly,’ said Rix.

‘You’ve got to come now.’

Sensing a shadow above him, Rix glanced up. The crevasse had been spanned with boards and Libbens was standing on them, staring malevolently down at Rix – no, at his lifeline. Grubs inched down Rix’s spine.

‘You can help the boy anytime!’ wept Dessin. ‘If you don’t get me out now, I’m a dead man.’

Rix gave him a cold stare and continued.

‘Please help Father,’ said the boy. ‘We need him bad.’

‘In a minute!’ Rix snapped. ‘Sorry, soldier,’ he added. ‘There’s only one way to do this, and that’s to be methodical.’

He finished the harness and called for the lad to be raised. When the rope came slithering down again in a splattering rain of mud and horse blood, Rix swung across and down another six feet to the second man.

‘It’s my turn, you mongrel!’ screamed Dessin.

The second man was a small, black-haired fellow with a long, bloody graze up his right thigh and hip, and another on his shoulder. His teeth were gritted, his face bloodless. His hips were trapped in a narrow part of the crevice and his legs hung oddly.

‘Where does it hurt, soldier?’ said Rix.

‘Think my hip’s busted,’ he said faintly. ‘Left leg, too.’

Rix probed the red-raw area. It was worse than that – both his pelvis and his left thigh bone were broken and, judging by the swelling and his blanched appearance, he was bleeding internally. With all those broken bones, lifting him would cause him agony.

Rix set to work, fashioning the best harness he could. It was so warm and humid down here that sweat was running down his face. He was stifling; he gasped at the dead air as if he could not get enough. What if he ended up trapped here ? What if the crevasse closed and squeezed him to death? He’d been a fool to come down. A leader had to lead, but only an idiot risked his life, and the fate of his army and country, playing the hero.

He fought an urge to abandon his men and flee hand over hand up the rope. The strong had a duty to help the weak. If no one else could do it, or would, he had to – leader or not.

‘There’s nothing I can do for you here,’ said Rix. Probably nothing anyone could do, even Holm, but you never knew.

‘He’s going to die anyway,’ sobbed Dessin. ‘And he’s a lazy, useless bastard, no loss to anyone.’

‘I’ll get to you in a minute, I said,’ Rix snapped.

Dessin twisted his upper body from side to side. ‘The crack’s gonna snap closed and squash me like a tomato, and I’ve got six kids to feed. Get – me – out!’

Rix completed the harness and bawled for the injured man to be heaved up. He was moving down the four feet to Dessin when the ground shook violently and the crevasse narrowed by a couple of inches. The hair stood up on Rix’s head – the gap on either side of him was only a couple of inches now. If he’d been side-on, the contraction would have broken both his collarbones.

Dessin howled, ‘It’s pinching my legs off. Do something, you stupid mongrel!’

Rix edged his way down. The soldier’s thighs were caught between ledges of harder rock jutting into the crevasse from either side, and when it had narrowed, the ledges had been forced into his flesh almost to the bones. He must be in agony. Blood was running down his legs … and if the crevasse narrowed any further …

Rix took hold of the Dessin’s right thigh and tried to work it free.

‘You bastard! You’re tearing my leg off.’

‘What would you have me do?’ Rix snapped.

‘If you’d come down fifteen minutes ago this wouldn’t have happened.’

Rix was thinking the same thing. Could he have saved Dessin if he’d come straight down? Possibly, though Rix was a bigger man; he could have been caught the same way.

‘Get me out!’

He contemplated knocking Dessin unconscious and dragging him out bodily. It would be quicker. But before he could move the ground shuddered violently, the crevasse contracted again and he heard an ominous snap. Dessin screamed.

Blood gushed from the stump of his left thigh. The pincer action of the closing ledges had sheared his left leg off and cut deep into the right thigh, though it was still held immovably. They were now confined in a space only ten inches wide and there was nothing Rix could do to save him – he could not tie on a tourniquet with his dead hand, nor could he turn to use his good hand. And if the crevasse closed by another two inches, they would die together.

Dessin took a deep, shuddering breath, then looked up at Rix and the anger was gone.

‘I’m a dead man, aren’t I?’ He had dark blue eyes; extraordinarily blue. The same eyes as his son.

‘Yes,’ said Rix, fighting his own panic. ‘You’re bleeding to death and I can’t stop it.’

‘Sorry for cursing you. The pain, it was unbearable. But it … it’s gone now.’

‘I’m glad.’ Rix clasped the soldier by the shoulder.

‘You’re a brave man, Deadhand, risking your life coming down here for us. The bravest I’ve ever met – I truly … truly believe you can save Hightspall. Get out, while you still can.’

‘I’ll not leave you to die alone,’ said Rix.

Dessin looked up. ‘I’ll die happier know you’re leading the army – and my three boys … and not him. Beware of him.’

A number of soldiers were on the planks now, looking down. He could not make out their faces, but even in silhouette he could see the rage emanating from the sacked general.

‘I will,’ said Rix.

He extended his hand and Dessin grasped it. There was no strength in his grip. Shortly his hand fell away and his head slumped.

‘Take care of my boys, won’t you?’ he whispered. ‘They’ve got to support their little sisters now.’

‘I’ll do my very best,’ said Rix. ‘Pull me up!’ he yelled.

No one moved. Were they going to leave him here? He looked down. The blood flow from the soldier’s severed thigh had slowed to a trickle and he was unconscious. Nothing could hurt him now.

‘Up!’ Rix bellowed.

The rope jerked him up, ten feet, twenty, thirty, forty and more, until he was next to Tonklin, who was still supporting his collarbone. The crack was wider here and Rix was able to turn sideways, though only just.

‘What are you doing here?’ said Rix. ‘They could have pulled you out fifteen minutes ago.’

‘Waiting for you.’

‘Then you’re a damn fool.’

‘I’m looking at a bigger one, if you don’t mind me saying so.’

Rix had no reply to that. He fashioned a harness around Tonklin’s chest and he was heaved away.

‘All right,’ called Rix. ‘Pull me up.’

The rope remained slack. All the watchers were gone except Libbens. He stood there, quite still, then stepped off the boards and out of sight.

The ground jerked up and down. Rix dropped sharply for fifteen feet, grazing his back painfully against the side of the crevasse, before stopping with a jerk that snapped his teeth together. What the hell was going on? Had the rope broken? No, it was still taut. Had they dropped him accidentally, or deliberately?

‘Pull me up!’ he yelled.

The rope did not move. Afraid to trust it now, he drew his knife, jammed it into the soil and levered himself upwards. After a couple of minutes of awkward, painful progress he had climbed a yard, but there were still six or seven to go.

Again the ground shuddered then, with a roar, part of the crevasse to his right collapsed. Rix climbed faster, the breath burning in his throat. Cracks were forming in the wall to his right; it was going to collapse any minute. He moved to the left, jammed the knife in as far as it would go, heaved up with all his weight, and the blade snapped.

The fall lost all the height he had gained, and more. He studied the rim of the crevasse above him, sweating. It had developed an ominous bulge. No way could he climb up there – he would bring the lot down on himself.

Libbens appeared on the planks again and spat in Rix’s direction.

‘It’s too dangerous,’ he said to the troops. ‘No man is worth risking the lives of a dozen.’ He waved an arm. ‘Leave him.’

He leapt off the plank, out of sight. Rix had no choice but to try and climb the rope, though he was at the end of his strength and climbing it one-handed was a mighty ask.

By jamming his steel-gauntleted right fist against the side of the crevasse, digging his toes in and heaving himself up the rope with his left hand, he managed to gain another three yards. Four to go, and he was exhausted, bone-deep. Dirt rained down into his eyes. As he wiped them, a lump of earth the size of his head struck him on the top of the skull so hard that it dazed him; it was all he could do to hang on.

A grinding sound issued up from the depths, then a hissing as of steam suddenly released. The whole crevasse was shuddering. If a geyser didn’t boil him alive, or tons of rock come down on his head, the crevasse would snap shut and squirt him out through the closing crack in a bloody fountain.

He was climbing desperately when the rope came tumbling down. The end had been neatly severed.

Libbens was making sure that he died here.

CHAPTER 3

Rannilt was too afraid to scream. In Cython, screaming had identified you as a victim. Prey!

Waves broke across the land, hurling boulders into the air. Trees thundered to the ground behind her; cracks opened in the ground then closed again; the air was full of dust, leaves and bark, and powdered stone.

Rannilt hunched over, whimpering, her whole body trembling. She clapped her hands over her ears but could not block out the roaring, grinding and crashing, as if the land was tearing itself to pieces. She sank onto her side, drew her knees up to her chest, wrapped her arms around them and rocked back and forth, eyes screwed shut.

Another tree fell, not far away. She let out a shriek – she couldn’t help herself. She had to get away. Rannilt scrambled up and bolted, having no idea where she was going. She ran until she could run no further but it did not stop. Was it the end of the world?

The ground went soft and sank beneath her feet. Water spurted from a red, split rock and a gust blew it into her face – hot water. A ragged crack opened up before her but, as she leapt it, the ground on the other side was thrust upwards and she slammed into the freshly made scarp. She fell and lay by the open crack, aching all over. It reminded her of the beatings she had suffered as a bullied slave girl in Cython, before she had met Tali, when no one in the world had cared if she lived or died.

Tali had saved Rannilt’s life; she had looked after Rannilt and taken her with her when she escaped. And through Tali, Rannilt had met Tobry, the kindest and gentlest man she had ever known. She ached for him, but he was gone, squashed beneath the tree.

Rannilt got up, rubbing her throbbing knees. They were bleeding. She plodded on, desperate to escape the chaos and the nightmare of the coming battle. Why were all those men planning to kill one another on the Plain of Reffering? It didn’t make any sense.

She was out in the grassland to the west, trudging along, when her scalp began to crawl. She whirled but there was nothing behind her. Rannilt went on, uneasily now, and soon felt the crawling sensation again. She knew not to ignore it; something dark, something foul was creeping through the long grass not far away.

She dared not run; she was afraid of making a noise that would attract it. Rannilt spied an ant hill fifty yards away and headed for it, crouched down. She crept around the far side, lay flat on the slope of the ant hill and carefully raised her head.

She saw him at once – an extremely tall, cadaverous man, dressed in black, about a hundred yards away. He was perfectly still, his head bent as if staring at the ground. He turned, scanning the grassland around him, and as his gaze swept across the anthill Rannilt felt that crawling sensation again, as if the top of her head was covered in maggots. It took all her strength to keep still while he stared at her hiding place. Could he make her out through the tall grass from so far away? She hoped not.

He went on, moving stiff-jointedly, studying the ground ahead. Rannilt had never seen him before but she knew who he was, for she had seen the light glinting off his opal eyes and his hideous black-opal teeth. He was Rufuss, one of the terrible Five Heroes. The most terrible of them all, she had heard: he was a broken man who preyed on people like her – the small, the weak and the defenceless. And he was searching for someone. No, hunting someone.

Hunting her? Surely not. Why would one of the Five Heroes hunt her? Ants were swarming all over her now, biting her on the legs and arms, but Rannilt did not move. She watched Rufuss until he disappeared from sight in a dip in the ground, then rose silently, brushed the ants off and scurried the other way. If he wasn’t hunting her, who was he after?

There was no way of knowing. She kept going in the opposite direction and, hours later, found herself at the ruins where she had camped last night with Rix, Glynnie, Tali and Holm. It was raining gently now, windy and very cold. She limped between the broken stone walls, hoping to find her friends, but the camp had been packed up. Nothing remained save the ash-filled fire pit and a broken chair Holm had fashioned from sticks bound together with wiry grass.

She was alone again.

Some of the masonry had been toppled by the quake but Rannilt spied a dry hole between the angle of two standing walls and the tumbled, mossy blocks of stone in front. She crept into the hole, into the darkest, tightest corner she could find, and wrapped her coat around her. It reminded her of hiding from the bully girls in Cython.

Having been hungry all her life as a slave, she pilfered food whenever she got the chance, and one of her coat pockets was full of stale bread and hard cheese. She ate a small portion of each, curled up and slept. That was another of her slave-girl skills. She could sleep anywhere.

Later on she heard distant shouting and the sound of thousands of people running like a herd, in panic. She did not look out. People did terrible things in war. If the enemy caught her, they might kill her like a rat, just for fun. Rannilt scrunched herself into an even smaller ball and did not make a sound.

Sometime after dark she was woken by a whimpering sound, though it was not the kind of whimper an injured dog made. This was a far bigger creature and it was badly hurt; it was dragging itself across the ground.

She dared not leave her hiding place, but she had to know what it was. She screwed her eyes shut, pressed her fingertips to the sides of her head and tried to sense the creature with her golden magery, that strange gift she had never understood. Her fingertips tingled and a momentary gleam illuminated her hidey hole, but she sensed nothing. Her gift had never worked properly since that terrible time in Lyf’s caverns, when he had drawn power out of her and nearly killed her.

Then, suddenly, Rannilt saw the creature in her mind’s eye: a shifter, but not a fierce one. It was crawling between a cluster of hovels, pulling itself along with one arm, with broken chains scraping and clanking behind it. Its other arm was bent at an odd angle, badly broken, and her heart went out to the poor, suffering creature.

She did not know where it was, though the nearest hovels had been at least a quarter of a mile away. The shifter looked around – a flash of yellow eyes – clawed at the ground and lurched through the rubble into a partly collapsed hovel. It was dark inside and she saw nothing save various still shapes on the floor, dead men and women.

The shifter shifted to a huge cat-like creature – a caitsthe, seven feet of deadly muscle. It crept to the nearest body and she heard a dreadful rending and gulping until a quarter of the body was gone. The shifter settled, closed its eyes. She must have slept as well, for when she next looked it was in man form again.

He sat up awkwardly, cradling his broken arm and wincing, which was odd – shifting usually healed injuries. There must be something badly wrong with him. The chains rattled and he looked around. It was lighter now and she could just make out the shapes on the floor, two dead men and a dead woman, further off.

He looked at the first man, who was partly eaten. The shifter stiffened, let out a howl of uttermost torment, then came to his knees and threw up violently. He looked around, wild-eyed, and she saw that it was Tobry. He was alive! His chains must have broken as the tree fell.

Rannilt could read the self-disgust in his eyes, the horrified realisation that he, once a decent and honourable man, had sunk so low that he had been feeding on the dead. His hands closed around his throat as if trying to choke himself to death. He squeezed for at least a minute, then his hands relaxed and he toppled over and lay there, weeping.

‘You poor thing!’ she whispered. ‘Stay there. I’m comin’.’

She crept out and stood up. She was sniffing the foggy air as if she could scent him out when Glynnie said, ‘There you are. I’ve been looking everywhere for you.’

She reached out to take Rannilt’s hand, and all Rannilt could see was another slave master ordering her around, trying to stop her from doing what she wanted more than anything in the world.

She sprang at Glynnie, slapping and scratching at her in a frenzy.

‘What’s the matter? Rannilt, it’s me! You’re safe now.’

Rannilt clawed at Glynnie’s face, shoved her over and ran blindly into the fog.

‘I can heal you,’ she cried. ‘I can, I can!’